Before There was Boogie Woogie, There was Blind Tom

by John Tennison, MD, October 5, 2011 (updated on July 19, 2015)

Before there was Rock And Roll, there was Boogie Woogie. Before there was Boogie Woogie, there was Blind Tom. Before there was Blind Tom, there was representation of steam locomotive sounds in published piano sheet music.

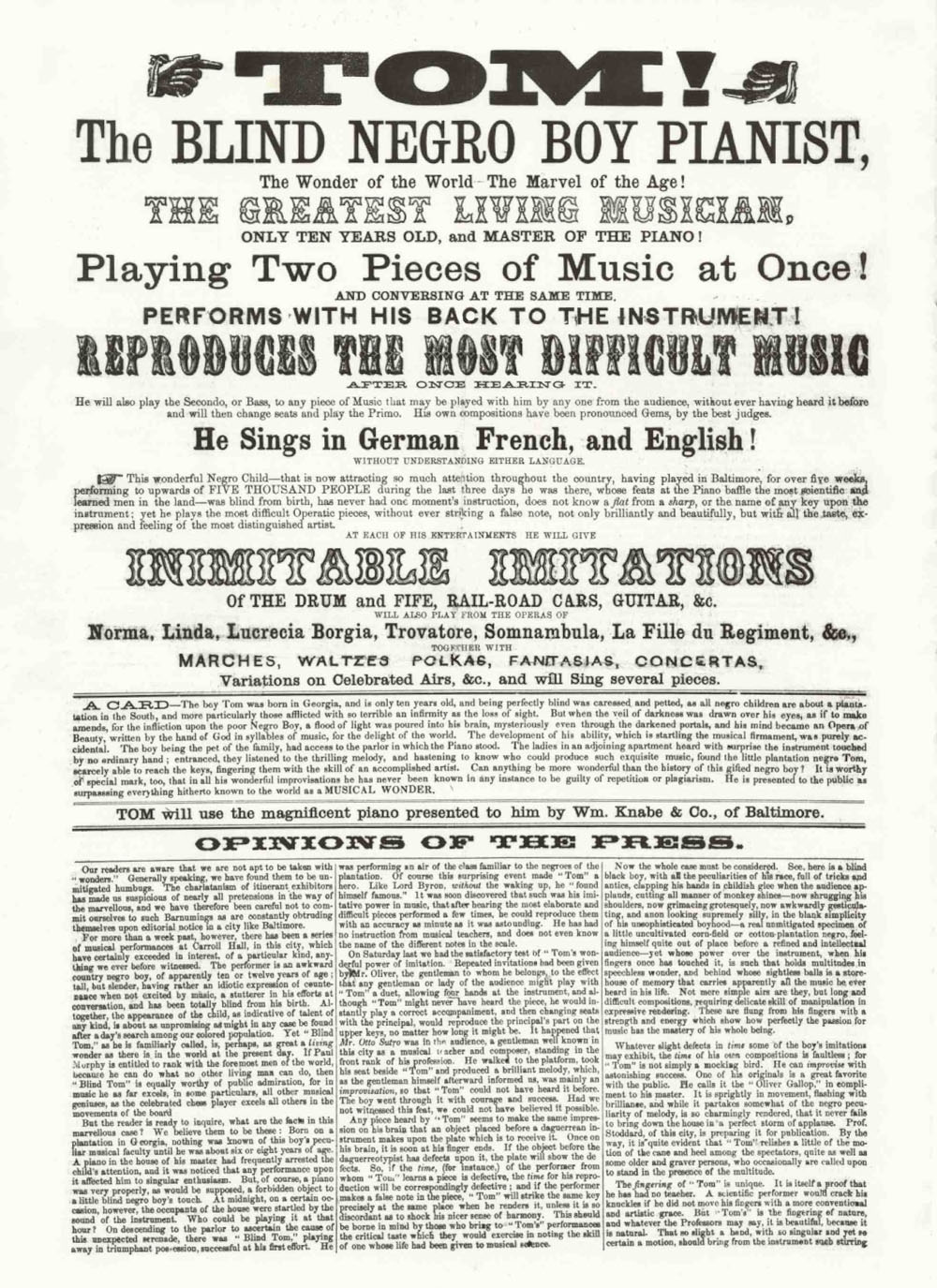

Blind Tom Poster from Either 1859 or 1860

Although I plan to have a considerable discussion of 19th-Century pre-Boogie Woogie influences in my book, I wanted to call attention at this time to one such possible influence: Blind Tom (AKA Thomas Wiggins).

Although I cannot find any evidence that what Wiggins played would have qualified as Boogie Woogie, I nonetheless find it entirely plausible that Wiggins might have influenced or inspired those who created Boogie Woogie. Moreover, given his ability to emulate what he heard, it would not be surprising if Wiggins heard Boogie Woogie and then played it at some point in his career.

I want to thank Deirdre O'Connell, author of the excellent book, "The Ballad of Blind Tom," 2009. Ms. O'Connell has been very kind to help clarify questions that I had about Blind Tom and to direct me to some of the primary sources that she used when writing her book. In addition to her book, I recommend her excellent website at:

I also want to thank musician and Blind Tom historian, John Davis, for his thoughts and clarifications of questions that I had about Blind Tom. John Davis has recorded an excellent album of Blind Tom's music. See:

Marshall, Texas is the earliest location in Texas where Blind Tom has been documented to have performed.

Blind Tom was already famous and was mentioned prominently in Texas newspapers in the 1860s. His two performances in Marshall, Texas on April 29 and April 30 of 1875 are the earliest known performances of Blind Tom in Texas that I have seen as of October, 2011. Blind Tom's presence in Marshall, Texas in 1875 allows for a possible in-person sharing of musical ideas with those who created Boogie Woogie.

Given the use of Blind Tom to promote morale among confederate troops during the Civil War, it is conceivable that Blind Tom could have come to Marshall, Texas or the Arklatex area during the Civil War, but without documentation, such a possibility seems unlikely.

Blind Tom's presence in Marshall, Texas in April, 1875 was uncovered by Nancy Canson, (see www.boogiewoogiemarshall.com ) while researching Boogie Woogie in July of 2010. Canson's research demonstrated that there were two performances by Blind Tom in Marshall, Texas (April 29 and April 30 of 1875), neither of which had been previously documented by Geneva Handy Southall (now deceased) in her extensive research culminating in three books on Wiggins. Consequently, Nancy Canson is now in the process of determining if there might be evidence of Wiggins in the Marshall area prior to 1875. (I want to thank Nancy Canson for her sharing the findings of her research.)

In the Decade from 1870 to 1880, Blind Tom appears to have performed more in Marshall, Texas than in any other Texas town.

Between 1875 and 1880, Blind Tom performed four or five times in Marshall, Texas. The performance dates in chronological order are as follows:

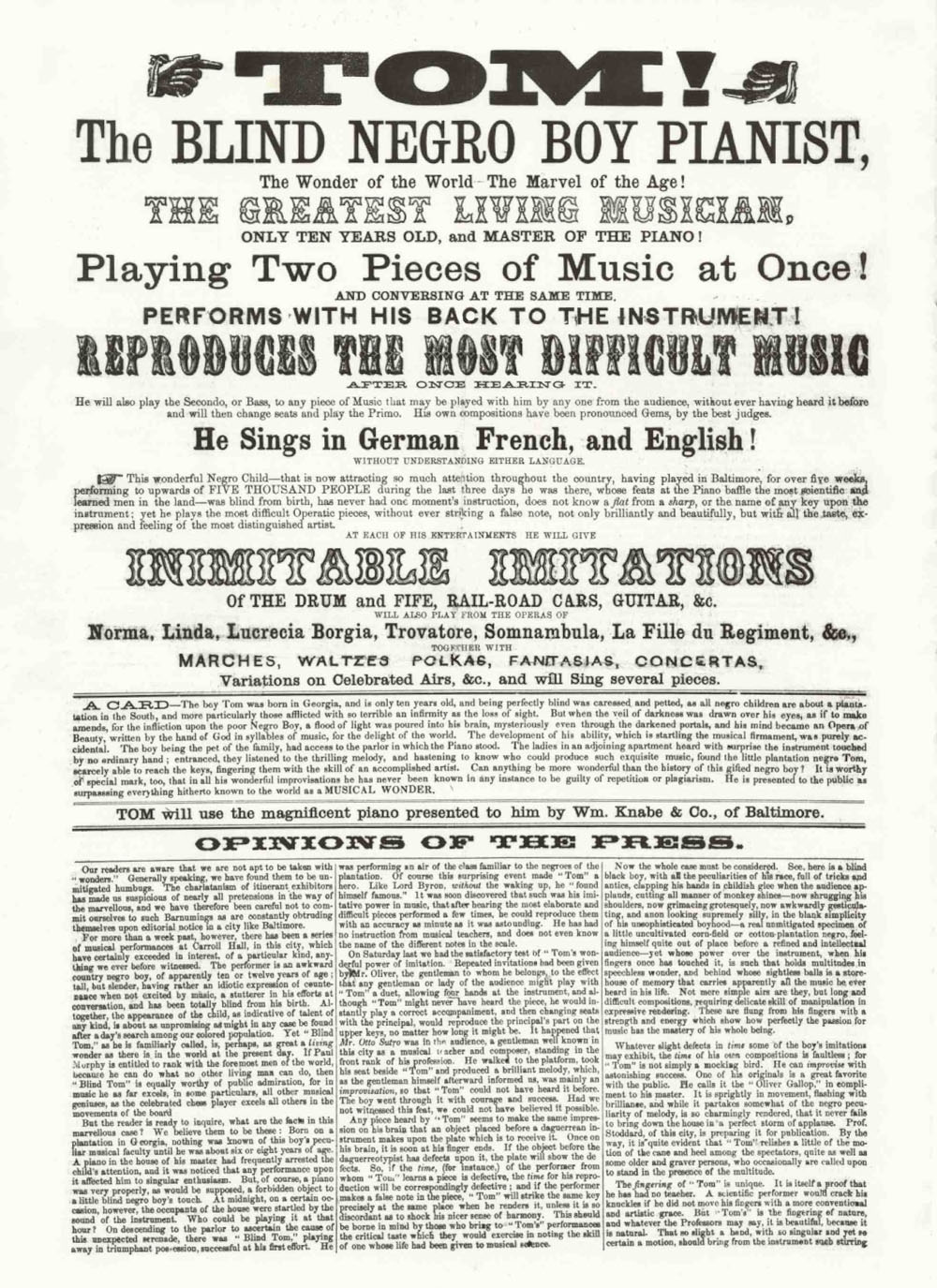

1. April 29, 1875 - Mahone's Opera House, Marshall, Texas

Newspaper Advertisement from the "Tri-Weekly Herald," in Marshall, Texas, April 29, 1875

(Discovered by Nancy Canson of Marshall, Texas, in July of 2010)

Nancy Canson's Transcription the 1875 Advertisement

2. April 30, 1875 - Mahone's Opera House, Marshall, Texas (Reference: In addition to the advertisement above, Nancy Canson discovered that the Saturday, May 1st, 1875 Tri-Weekly Herald had a news item under "Local" which indicated that Blind Tom made a repeat performance on Friday (April 30th, 1875) at 10 o'clock by Special Request.)

3. Circa February 2, 1878 - Mahone's Opera House, Marshall, Texas (Reference: page 188 of Southall's second book, where Southall writes "Malone Opera House," which almost certainly was a spelling error.)

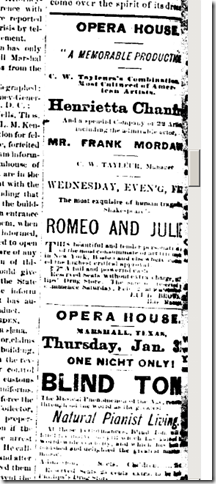

On July 3, 2015, Jack Canson of Marshall Texas shared a newspaper article that he discovered while researching 19th-Century Newspapers. Jack Canson discovered a January 29, 1878 newspaper advertisement from the Tri-Weekly Herald which indicated that Blint Tom was going to be performing for one night only on January 30, 1878 at the "OPERA HOUSE" in Marshall, Texas. This performance is probably the one that I had listed above as "Circa February 2, 1878." However, it is possible that Blind Tom stayed in Marshall for a repeat performance on February 2, 1878, just as he had done on April 30, 1875.

Newspaper Advertisement from the "Tri-Weekly Herald," in Marshall, Texas, January 29, 1878

(Discovered by Jack Canson of Marshall, Texas, on July 3, 2015)

4. May 6, 1880 -- (Presumably at) Mahone's Opera House, Marshall, Texas (Reference: page 202 of Southall's second book).

Did Blind Tom Play Boogie Woogie?

I have not seen evidence that Wiggins himself was the first to play what would qualify as Boogie Woogie; nor have I seen claims that Wiggins played Boogie Woogie at any point in his career. However, given his ability to emulate what he heard, it would not be surprising if Wiggins heard Boogie Woogie and then played it at some point in his career.

On page 12 of the March 1946 issue of the Record Changer magazine, Ernest Borneman wrote the following:

"A few weeks ago I asked Sox Wilson what was the first blues he ever heard in his life, and when he played it, he used a walking bass. When I asked him how old he thought the tune was, he said that he had heard his father play and sing it and that it probably went back to the early or middle nineteenth century. Handy confirms that Blind Tom (Thomas Greene Bethune), who was born in 1849, used to play the blues with the same rolling bass Handy later heard in Memphis where Seymour Abernathy, Benny French and Sonny Butts used it in the Beale Street joints from which Handy took the inspiration for his Memphis Blues and Beale Street Blues."

Moreover, on page 85 of the chapter, "Struttin' That Thing," in his 1969 book, "The Story of the Blues," Paul Oliver writes:

"Morton had a poor opinion of Benny Frenchy as a pianist but W. C. Handy, who had an ear for the folk blues, heard and noted the figures which Benny Frenchy, Sonny Butts and Seymour Abernathy played with their 'eight-to-the-bar pre-influence' of boogie-woogie."

At first, a reading of Oliver's comments would suggest to some that the eight-to-the-bar quality of the music that Handy heard in St. Louis was a property of the left hand bass figures, as is the case with much of Boogie Woogie. However, Handy's autobiography seems to indicate otherwise on page 155, where a musical manuscript of "Beale Street Blues" is printed, and where Handy writes the following:

"'Eight to the bar' ("boogie-woogie") pre-influence with jazz interpolations are shown in the right hand."

Moreover, the left handed bass figures for "Beale Street Blues" manuscript contain some measures which could be considered a "rolling bass," but also contain some measures which are standard 2-beat oom-pahs. In only 1 measure does the left-handed part contain what approaches an 8-beat-to-the-bar figure. (Two of the 8th notes are tied together to create a quarter note, leaving 6 remaining 8th notes in the measure.) Moreover, the left-handed part of "Beale Street Blues" is not a perpetual ostinato of the sort seen in Boogie Woogie.

So even if Blind Tom did play Boogie Woogie, it appears that the "rolling" bass figure that Handy heard Blind Tom play was possibly not a bass figure that could be considered a Boogie Woogie bass figure, but rather a non-ostinato bass figure similar to what Handy used in "Beale Street Blues."

However, even if Handy had heard Blind Tom played a bass figure that could be considered a Boogie Woogie bass figure, the simple fact of playing a "rolling bass" or an ostinato 8-to-the-bar bass figure on a piano and possibly regarding it as representing a steam locomotive is not sufficient to make something "Boogie Woogie." That is, Boogie Woogie also requires that there be a certain type of relationship between the right and left hand parts such that the specific type of polyrhythm known as cross-rhythm is created. Nonetheless, the music of Wiggins clearly had elements that were in common with Boogie Woogie. Consequently, these properties of Blind Tom's music might have inspired or influenced those who created Boogie Woogie. These properties are described below in the sections below.

The fact that Blind Tom played "rolling bass" figures is not evidence of his necessarily having created them. That is, he could have easily heard them and picked them up at one of the many towns he visited. For example, it is plausible that Blind Tom could have heard Boogie Woogie bass figures for the first time when he came to Marshall, Texas in 1875.

A line of thought that suggests that Blind Tom did not play Boogie Woogie is the fact that Ernest Borneman was obsessed with trying to determine the origin of Blues and Boogie Woogie. It's hard to believe that Borneman would not have discussed ideas about the origin of Boogie Woogie with W. C. Handy. Moreover, if W. C. Handy had mentioned hearing Blind Tom play something that could have been considered "Boogie Woogie," Borneman would have almost certainly have written about it. Moreover, many individuals (both black and white) were interviewed during the early part of the 20th century in the early years of research on the origin of Boogie Woogie. Despite the fact that the individuals interviewed would have been alive and likely have had the opportunity to have witnessed one or more Blind Tom performances; and despite the widespread fame of Blind Tom, no one interviewed, including W. C. Handy, appears to have mentioned Blind Tom as having played anything that they considered "Boogie Woogie."

Representation of Steam Locomotive Sounds in Published Piano Sheet Music Prior to the Birth of Blind Tom

The representation of steam locomotive sounds in published piano sheet music was well established prior to the birth of Blind Tom in 1849. One example is Joseph Gung'l's "Rail Road Galopade," which was published in 1847. Here is the first page of "Rail Road Galopade," where ostinato is used in both the left and right hands under the descriptive label "Noise of the Locomotive."

"Noise of the Locomotive" -- Page 1 of "Rail Road Galopade" (Published in 1847)

Another prominent example prior to the birth of Blind Tom is "Harnden's Express Line, Gallopade & Trio," composed by A. R. , and published in 1841. (I don't know who "A. R." was.)

"Harnden's Express Line, Gallopade & Trio" -- Cover -- Published in 1841

"The Bell and Locomotive." -- Page 3 of "Harnden's Express Line, Gallopade & Trio" -- Published in 1841

Note the description on page 3 above: "The Bell and Locomotive."

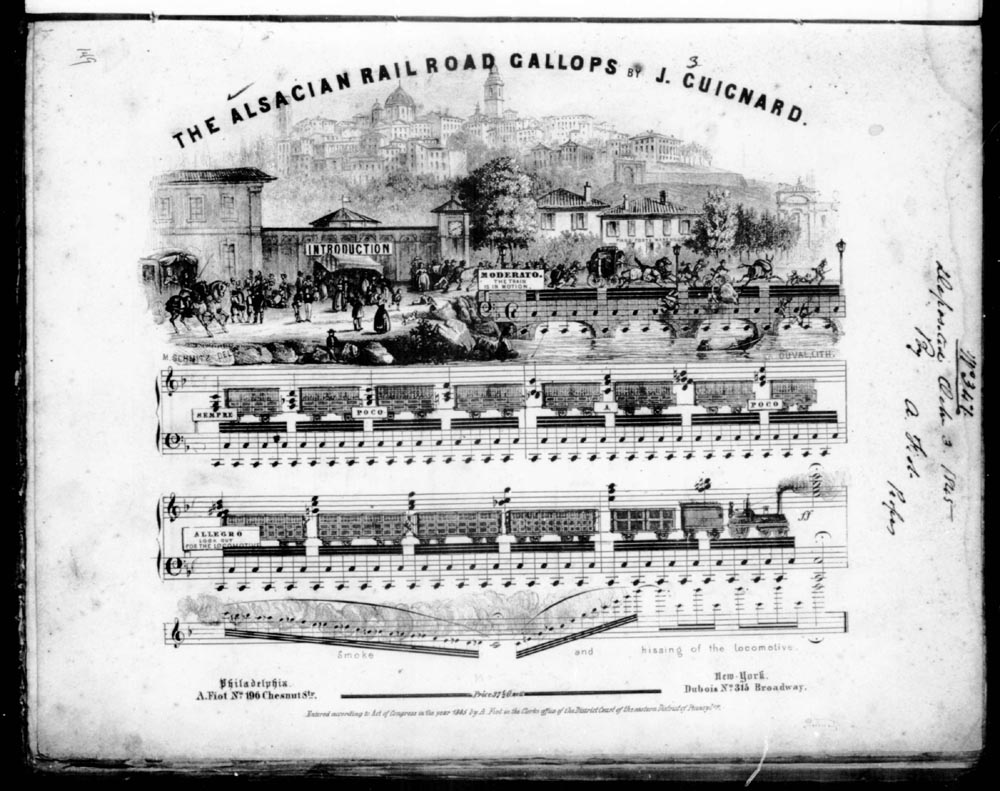

Another example prior to the birth of Blind Tom is the beautifully-drawn first page of "The Alsacian Railroad Gallops," by J. Cuicnard, published in 1845, and like Gung'l, also uses ostinato.

"Smoke and hissing of the locomotive" -- Page 1 of "The Alsacian Railroad Gallops" (Published in 1845)

Note the description at the bottom of the page above: "Smoke and hissing of the locomotive."

Although it did not contain descriptions of specific locomotive sounds being represented, Christopher Meineke's "Rail Road March," published in 1928, is clearly an example of published piano sheet music which is "about" a train. This piece was dedicated to the directors of Baltimore & Ohio Rail Road.

"Rail Road March" by Christopher Meineke (Published in 1828)

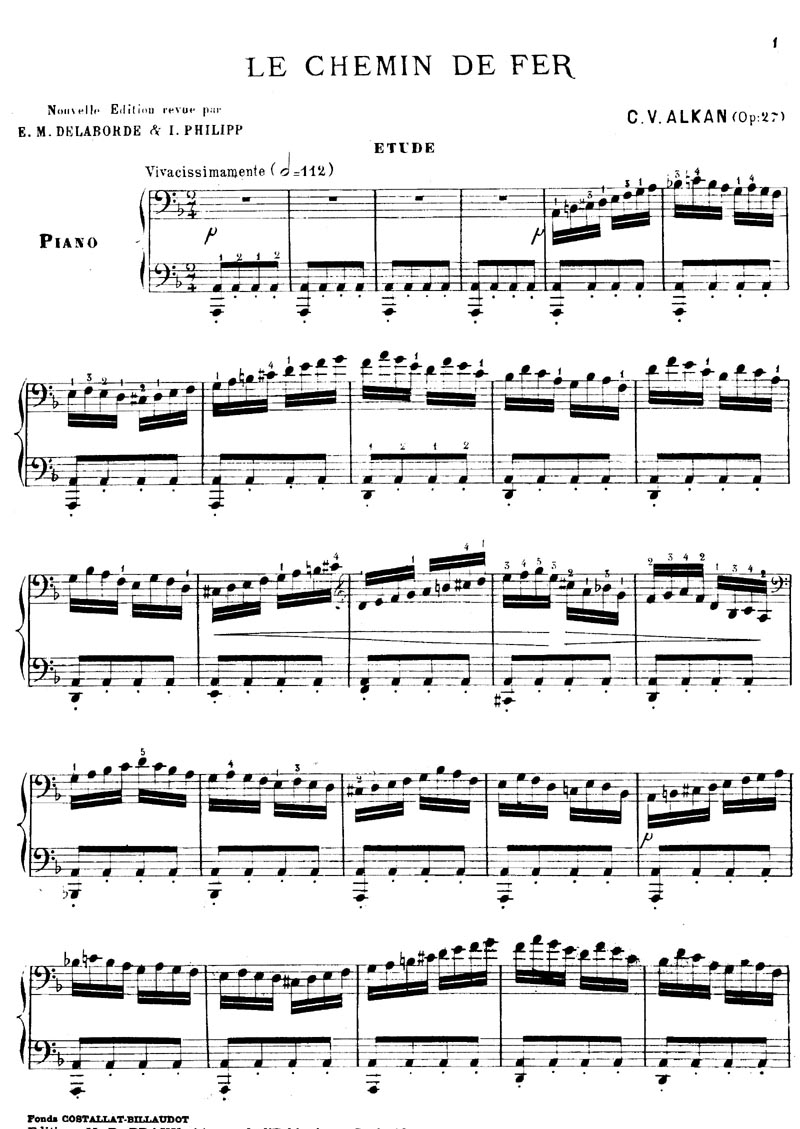

One of the most famous musical compositions from the 1840s which represented a steam locomotive is Charles-Valentin Alkan's "Le Chemin De Fer" (French for "The Railway"), which was published in 1844. Although some historians think it might have been a typographical error, the tempo notation of 112 half-notes per minute has resulted in this piece being played at blazingly fast speeds by those who are skillful enough to do so. Some historians believe the tempo was intended by Alkan to be 112 quarter notes per minute.

Le Chemin De Fer (French for "The Railway") Op. 27, by Charles-Valentin Alkan (Published in 1844)

The Idea of Representing Steam Locomotive Sounds on a Piano

Even if the earliest Boogie Woogie bass figures did not resemble the ostinato figures used by Wiggins and others before him to represent steam locomotive sounds on a piano, it is still plausible that the idea to represent sounds related to steam locomotives on a piano (by ostinato or otherwise) could have come from Blind Tom Wiggins or others before him. However, given the relative remoteness of Texas logging and railroad camps as compared to the typical in-town locations (Opera Houses, etc.) where Wiggins and published piano music was typically performed, it is also plausible that the idea to represent the sounds related to steam locomotives on a piano (by ostinato or otherwise) could have occurred independently of any knowledge of or exposure to Tom Wiggins or to others who had previously represented locomotive sounds in piano music prior to Blind Tom.

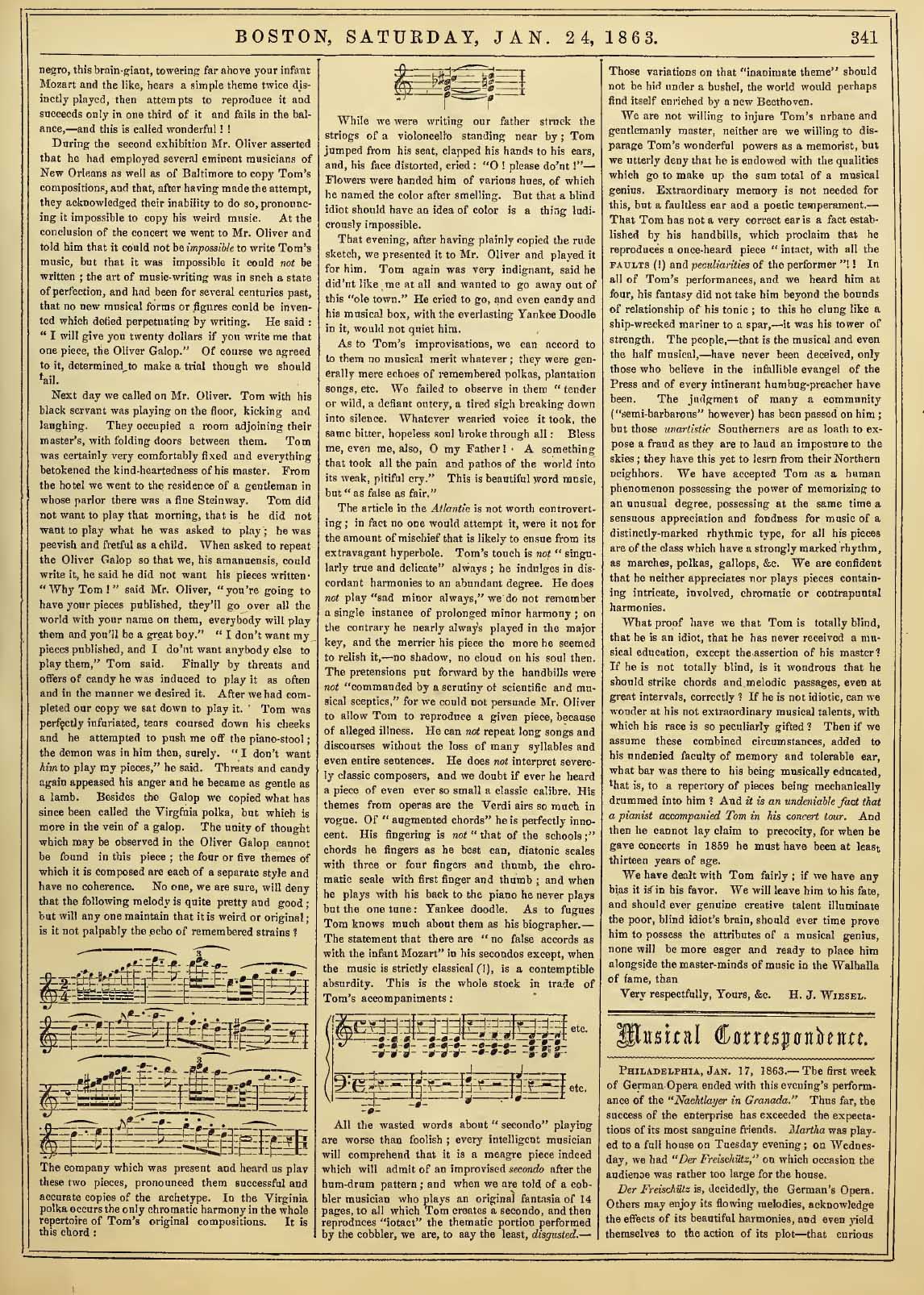

A Description of Blind Tom's Use of Simultaneous Vocal and Piano Ostinato to Represent the Steam Locomotive in 1860

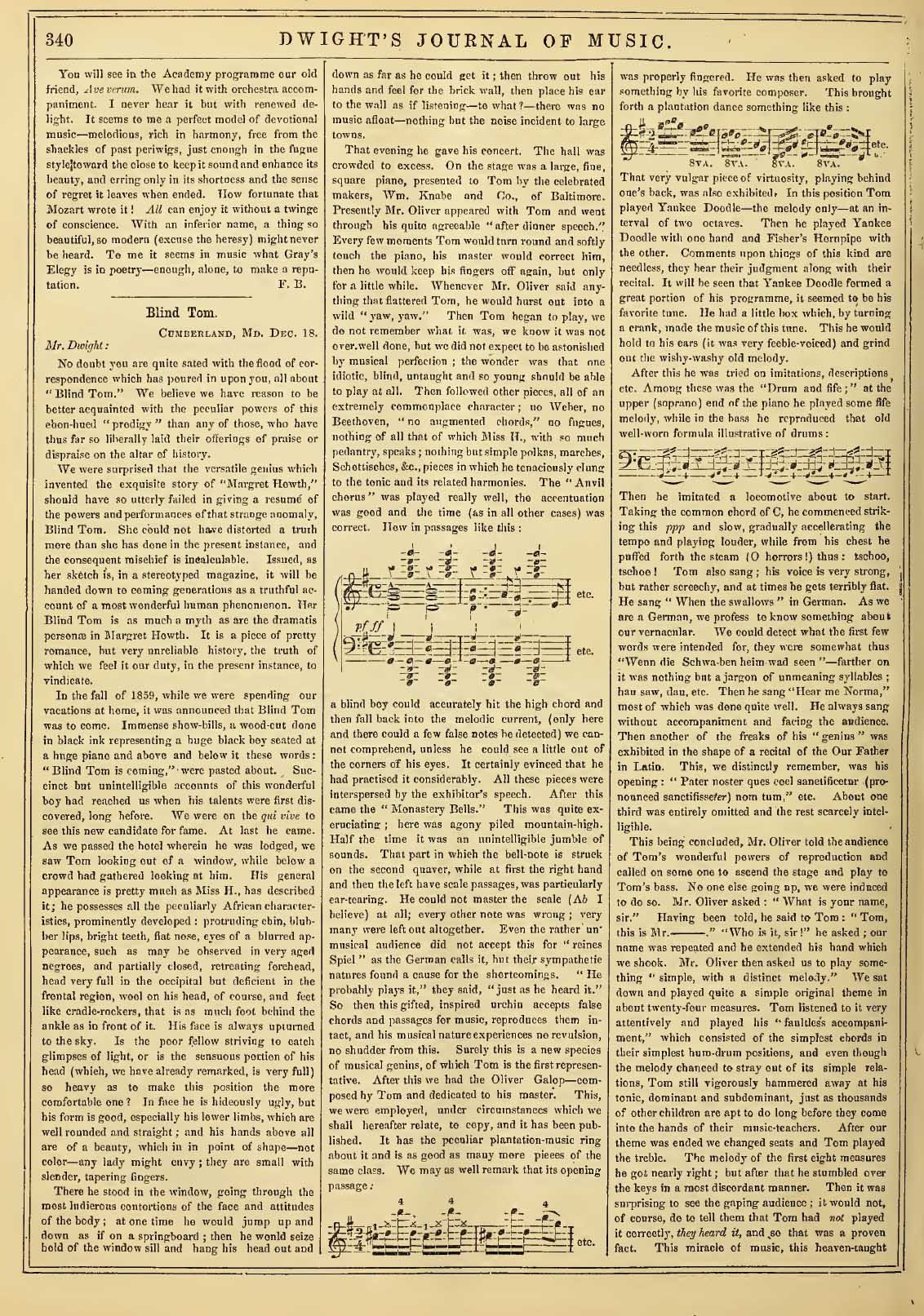

H. J. Wiesel, the literate musician who transcribed some of Blind Tom's early music, wrote an article containing what might be the first published description of Blind Tom's musical representation of a steam locomotive during a Blind Tom concert. As can be seen from the middle of the third column on page 340 of January, 24, 1863 issue of Dwight's Music Journal (see 2 scans of pages 340-341 below), Wiesel wrote the following:

"Then he imitated a locomotive about to start. Taking the common chord of C, he commenced striking this ppp and slow, gradually accelerating the tempo and playing louder, while from his chest he puffed forth the steam (O horrors!) thus: tschoo, tschoo!"

It is possible that dramatic vocal representations of sounds associated with trains were occurring prior to those of Blind Tom. However, as of August 10, 2012, I have not yet seen evidence for such vocal performances prior to those of Blind Tom as described by H. J. Wiesel in 1860.

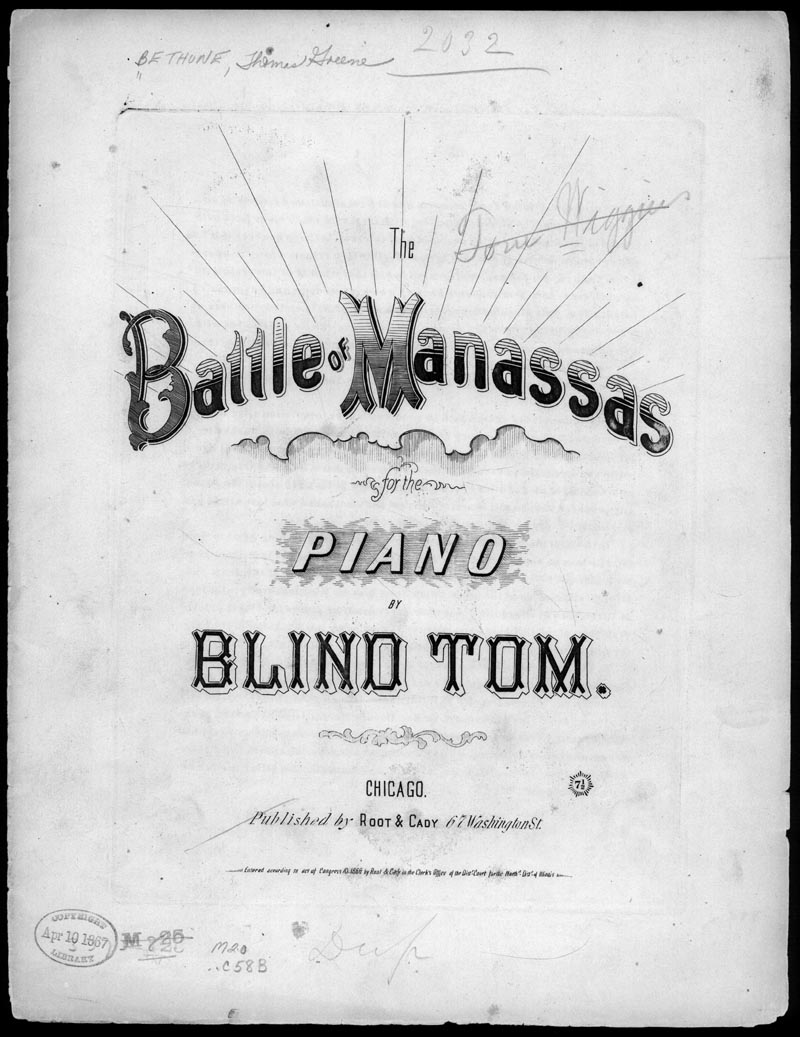

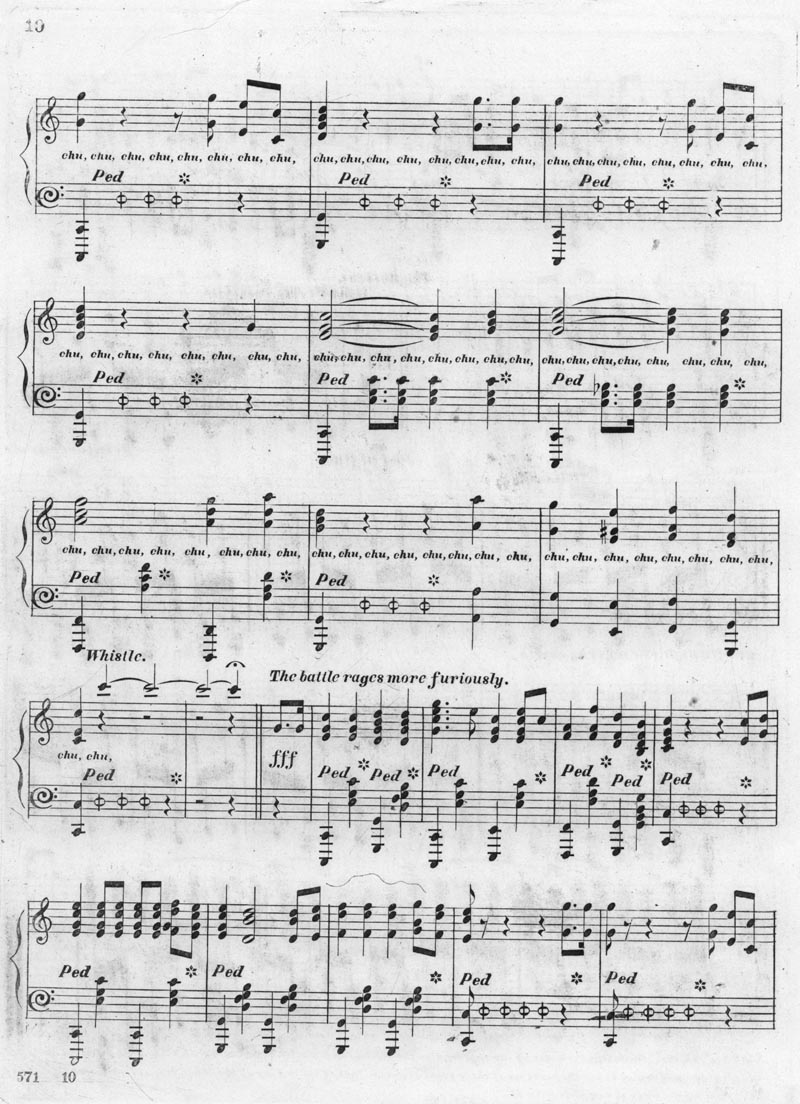

Blind Tom's "Battle of Manassas" (Published in 1866)

I don't know the ethnic identity of all composers who represented train sounds in published music prior to the birth of Blind Tom in 1849. Consequently, I cannot be sure if Wiggins was the first African American to represent steam locomotive sounds in a piece of published sheet music when he published "Battle of Manassas" in 1866. However, it is possible that "Battle of Manassas" was the first published piano sheet-music title by an African American in which steam train sounds were represented.

Battle of Manassas - Cover

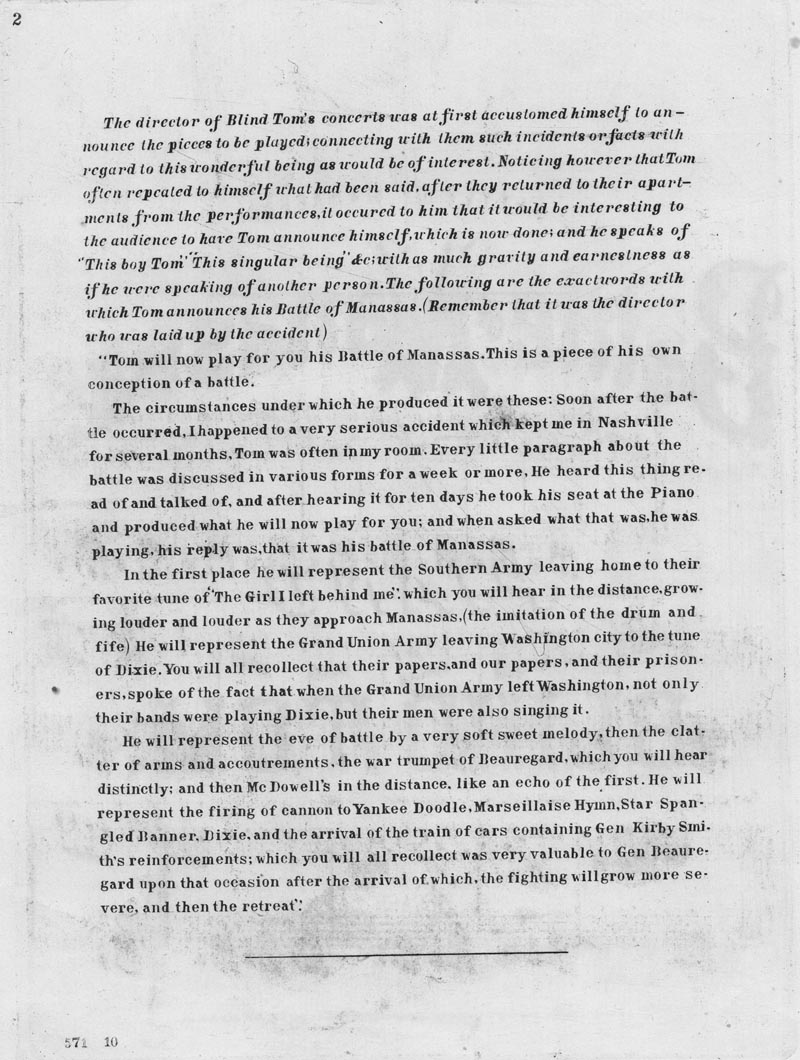

Battle of Manassas - Page 2

Notice the last paragraph above in which is stated of Blind Tom: "He will represent the firing of cannon to Yankee Doodle, Marseillaise Hymn, Star Spangled Banner, Dixie, and the arrival of the train of cars containing Gen Kirby Simth's reinforcements;...."

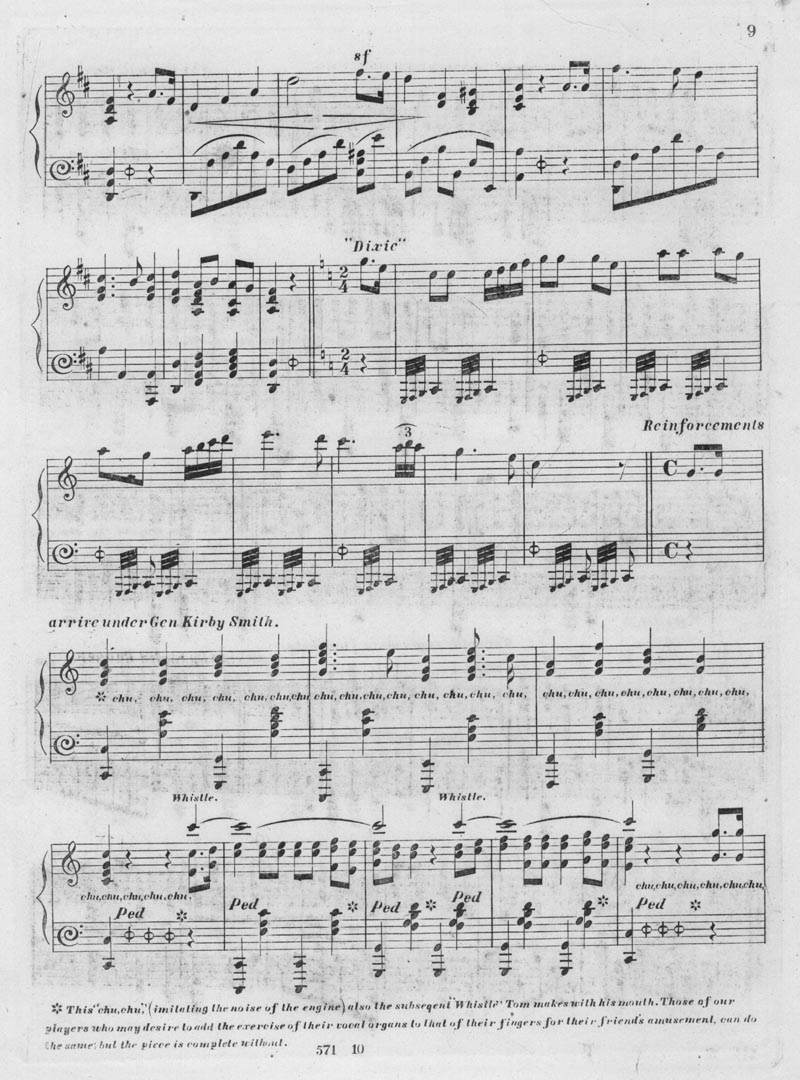

Battle of Manassas - Page 9 - Reinforcements arrive under Gen Kirby Smith.

Battle of Manassas - Page 10

Here's a vivid description by Mark Twain of a vocal and bodily train representation by Blind Tom when Twain first encountered him on a train in 1869:

"One day last winter I was on my way from Galena to another Illinois town to fill a lecture engagement. I went into the smoking car and sat down to meditate; but it was not a good meditating place, for pretty soon a burly negro man on the opposite side of the car began to sway his body violently forward and back, and mimic with his mouth the hiss and clatter of the train, in the most savagely excited way. Every time he came forward I was sure he was going to brain himself on the seat-back in front of him, and every time he reversed I was as certain he was going to throw a back-somersault over his own seat. What a wild state he was in! Clattering, hissing, whistling, blowing off gauge cocks, ringing his bell, thundering over bridges with a row and a racket like everything going to pieces, whooping through tunnels, running over cows -- Heavens! I thought, will this devil never run his viewless express off the track and give us a rest? No, sir. For three dreadful hours he kept it up -- and you may know by that what muscles and what wind he had. His wild eyes were sightless. For the most part he kept his head turned sideways and upward as blind people usually do who get a dim ray of light from apparently above the eye somewhere. He kept his face constantly twisted and distorted out of all shape. When he spoke he talked excitedly to himself, in an idiotic way and incoherently, but never slowed down on his imaginary express train to do it. He looked about thirty, was coarsely and slouchily dressed, and was as ungainly in build and uncomely of countenance as any half-civilized plantation slave. After I had endured his furious entertainment until I was becoming as crazy as he was and getting ready to start an opposition express on my own hook, I inquired who this barbarian was, and where he was bound for, and why he was not chained or throttled? They said it was Blind Tom, the celebrated pianist -- a harmless idiot to whom all sounds were music, and the imitation of them an unceasing delight. Even discord had a charm for his exquisite ear. Even the groaning and clattering and hissing of a railway train was harmony to him. And this stalwart brute was to torture his muscles all day with this terrific exercise, and then instead of lying down at night to die of exhaustion, was to sit behind a grand piano and bewitch a multitude with the pathos, the tenderness, the gaiety, the thunder, the brilliant and varied inspiration of his music!"

The First Documented Beat Boxer

The vocalizations of Blind Tom Wiggins appear to be the first documented evidence of what could rightfully be considered "Beat Boxing," or vocal percussion as heard in modern-day rap and some other styles of music.

Use of Ostinato

Like Gung'l and others before him, Blind Tom used ostinato to represent train sounds.

Use of Accelerando and Dynamic Changes

The most sophisticated Boogie Woogie players, like classical musicians more generally, make use of accelerando and dynamic changes, for which Wiesel's description Blind Tom also used in his steam locomotive representation.

Use of Tone Clusters

Wiggins might also have been the first musician to notate "tone clusters" in piano music, as occurs in his "Battle of Manassas," which in this piece, were used to represent cannon fire. Although it is not clear that Wiggins ever used tone clusters to represent the sound of a steam locomotive, tone clusters have the capacity to sound more similar to the actual chuffs of a steam locomotive than typical Boogie Woogie bass figures. Moreover, tone clusters became common-place in Boogie Woogie music, and can be heard prominently in the right-hand parts of music of Meade Lux Lewis. (For an example, listen to Lewis's excellent "Bush Street Boogie" and "Hangover Boogie.")

Independence of Hands, with the Possibility of Polyrhythm of the Cross-Rhythm Sub-Type

Blind Tom Wiggins was also known to be able to play different melodies in the left and the right hand at the same time. For example, Blind Tom would play "Fisher's Hornpipe" and "Yankee Doodle" simultaneously.

Most musicians of moderate skill can do this. For example, page 203 of Southall's 2nd book indicates that Blind Boone incorporated it into his performances.

Cross-rhythm is the specific type of polyrhythm defined by the relationship between the left and right hands in Boogie Woogie.

To qualify as a cross-rhythm, there must be two different metric pulses, or frames of reference, which have an irrational-number ratio to each other. So, 3-on-2 would create cross-rhythms. If either time-division (2 or 3) when used in the numerator and divided by the other number results in an irrational number, then a cross-rhythm is generated. So even though 3 divided by 2 is not an irrational number, 2 divided 3 is, and thus, playing 3-on-2 or 2-on-3 would generate cross rhythms. Although such divisions as 2-on-8, or 4-on-8, or 16-on-8 can allow for different rhythms at the same time (technically "polyrhythm"), ratios between these two time frames are not irrational numbers, and do not give the same feel or the sense of as great of a magnitude of independence of hands as experienced when cross-rhythms are being used.

Unless Blind Tom was altering the traditional rhythm of either "Fisher's Hornpipe" and/or "Yankee Doodle", playing them at the same time would not have resulted in polyrhythm of the cross-rhythm subtype because the melodies of these two pieces do not allow for two different metric frames-of-reference which have an irrational-number ratio to each other.

The structure of either "Fisher's Hornpipe" and "Yankee Doodle" would lend itself well to a left-handed ostinato bass figure. However, I have found no evidence that Blind Tom played either one of them as an ostinato figure in the left-hand.

Blind Tom's independence of hands and the possibility of having generated polyrhythm of the cross-rhythm subtype could have plausibly inspired the earliest Boogie Woogie players to play in ways exhibiting the high degree of independence of hands, and to have generated subsequent cross-rhythms, even if Blind Tom himself had not played using cross-rhythms.

Improvisation on a Piano

Although it's certainly not the case that improvisation on a piano was invented by Blind Tom, it is nonetheless plausible that the extent to which Blind Tom improvised, and the fact that such improvisations were highly advertised, could have influenced the earliest Boogie Woogie players to play in ways that were spontaneous and highly idiosyncratic. However, it also seems just as plausible that these attributes of Boogie Woogie could be explained by a widespread African American stylistic tendency to play improvisationally that would have been present with or without Blind Tom.

Future Updates

There is much more that I would like to write about Wiggins, so I will be updating this article from time to time. Thanks to Andrew Petrou, Boogie Woogie musician in Australia whose interest, ideas, and enthusiasm for Boogie Woogie and thoughts about Blind Tom convinced me that I should have some coverage of Blind Tom Wiggins on the www.bowofo.org website as of 2011, rather than wait to put such material only in my book.