BOOGIE WOOGIE:

Its Origin, Subsequent History, and Continuing Development

Copyright 2004-2015 by John "Nonjohn" Tennison, M.D. All Rights Reserved This article was last updated on August 9, 2015.

(This article is a draft that contains only a fraction of the material that I will eventually publish as a book. Some sections and references in this article are incomplete and will be expanded in the book, including never-before-published material from field research on Boogie Woogie by me and others.)

“There is every reason for us to know something about Africa and to understand its past and the way of life of its peoples. Africa is a rich continent that has for centuries provided the world with art, culture, labor, wealth, and natural resources.”73

and

“But perhaps most important is the fact that fossil evidence indicates that human beings originated in Africa”73

and

“To be human is to be of African descent.”73

-- George C. Bond, Ph.D., Director, Institute of African Studies, Columbia University, (page 6 of the book, "Chokwe")73

Moreover, music historian, Dave Oliphant has written:

"Barrelhouse, boogie-woogie, and jazz all originate to some degree in the religio-sexual customs of primitive African societies, for Wilfrid Mellers14 notes, one of the meanings of the phrase 'boogie-woogie,' and of the word 'jazz' itself, is sexual intercourse, even as the ritualistic-orgiastic nature of the music also represents an ecstatic form of a spiritual order."13

Thus, as I consider Boogie Woogie, I intend to remain ever mindful that we are all of African descent. Being mindful of this fact suggests certain questions: For example, does Boogie Woogie have its widespread and lasting appeal because of any universal, evolutionary and/or instinctual aesthetic that has been biologically inherited by all human beings? Is there historical and cultural evidence in Africa even today that suggest a common biological heritage and aesthetic sensibility among human beings? If so, what are the elements of this common aesthetic? Does Boogie Woogie share any of these elements? Have the pretensions of so-called “civilization” created historical contexts where some human beings have unknowingly denied their own capacity to appreciate Boogie Woogie? To the extent that these questions can be answered in the affirmative, Boogie Woogie can be seen in a much larger context than merely being a popular music and dance form originating in the United States. However, before considering Boogie Woogie in such a broad historical context, I want to first examine its evolution within the United States.

Barrelhouse Pianist

The photo above was taken in Minglewood, TN in 1920. This photo is contained in the Special Collections Photograph Archives of the University of Louisville.

“Boogie Woogie piano playing originated in the lumber and turpentine camps of Texas and in the sporting houses of that state. A fast, rolling bass—giving the piece an undercurrent of tremendous power—power piano playing."

"Neither Pine Top Smith, Meade Lux Lewis nor Albert Ammons originated that style of playing—they are merely exponents of it."

"In Houston, Dallas, and Galveston—all Negro piano players played that way. This style was often referred to as a 'fast western' or 'fast blues' as differentiated from the 'slow blues' of New Orleans and St. Louis. At these gatherings the ragtime and blues boys could easily tell from what section of the country a man came, even going so far as to name the town, by his interpretation of a piece.”1 -- E. Simms Campbell, 1939, pages 112-113, (in Chapter 4 "Blues") in the book, "Jazzmen: The Story of Hot Jazz Told in the Lives of the Men Who Created It"1

Consistent with the findings of E. Simms Campbell are the comments of Elliot Paul, who wrote the following on page 229 in 1957 (in Chapter 10 "Boogie Woogie ") in his book "That Crazy American Music"78:

"The first Negroes who played what is called boogie woogie, or house-rent music, and attracted attention in city slums where other Negroes held jam sessions, were from Texas. And all the Old-time Texans, black or white, are agreed that boogie piano players were first heard in the lumber and turpentine camps, where nobody was at home at all. The style dates from the early 1870s. Even before ragtime, with its characteristic syncopation and forward momentum, was picked up by whites in the North, boogie was a necessary factor in Negro existence wherever the struggle for an economic foothold had grouped the ex-slaves in segregated communities (mostly in water-front cities along the gulf, the Mississippi and its tributaries)."78

Note: Despite the fact that both E. Simms Campbell and Elliot Paul mention "turpentine camps," there is good reason to conclude that Boogie Woogie did not originate in turpentine camps. For a more detailed explanation of the reasoning that led to this conclusion, see the section titled "Why Boogie Woogie Is Unlikely to Have Originated in Turpentine Camps."

On page 2 of his 1940 "Boogie Woogie and Blues Folio,"63 in his annotation to the reprint of the 1923 sheet music of George W. Thomas, Jr.'s "New Orleans Hop Scop Blues," (first published in 1916 by George W. Thomas) Clarence Williams states:

"The 'Boogie Woogie' originated in Texas many years ago. It wasn't called the 'Boogie Woogie' then. George Thomas was the fellow who used this style and first wrote it down."63

George W. Thomas, Jr.

This image of George Washington Thomas, Jr., is from Page 2 of Clarence Williams' 1940 "Boogie Woogie and Blues Folio"63

"Texas as the state of origin became reinforced by Jelly Roll Morton who said he heard the boogie piano style there early in the century; so did Leadbelly and so did Bunk Johnson."74 -- 1983, Rosetta Reitz [Leadbelly reported hearing Boogie Woogie in 1899. -- see section on Leadbelly below.]

Steel Gang Laying a Logging Railroad in the Piney Woods of East Texas

(From the East Texas Research Center Collection)

Click here to go to the website of the East Texas Research Center.

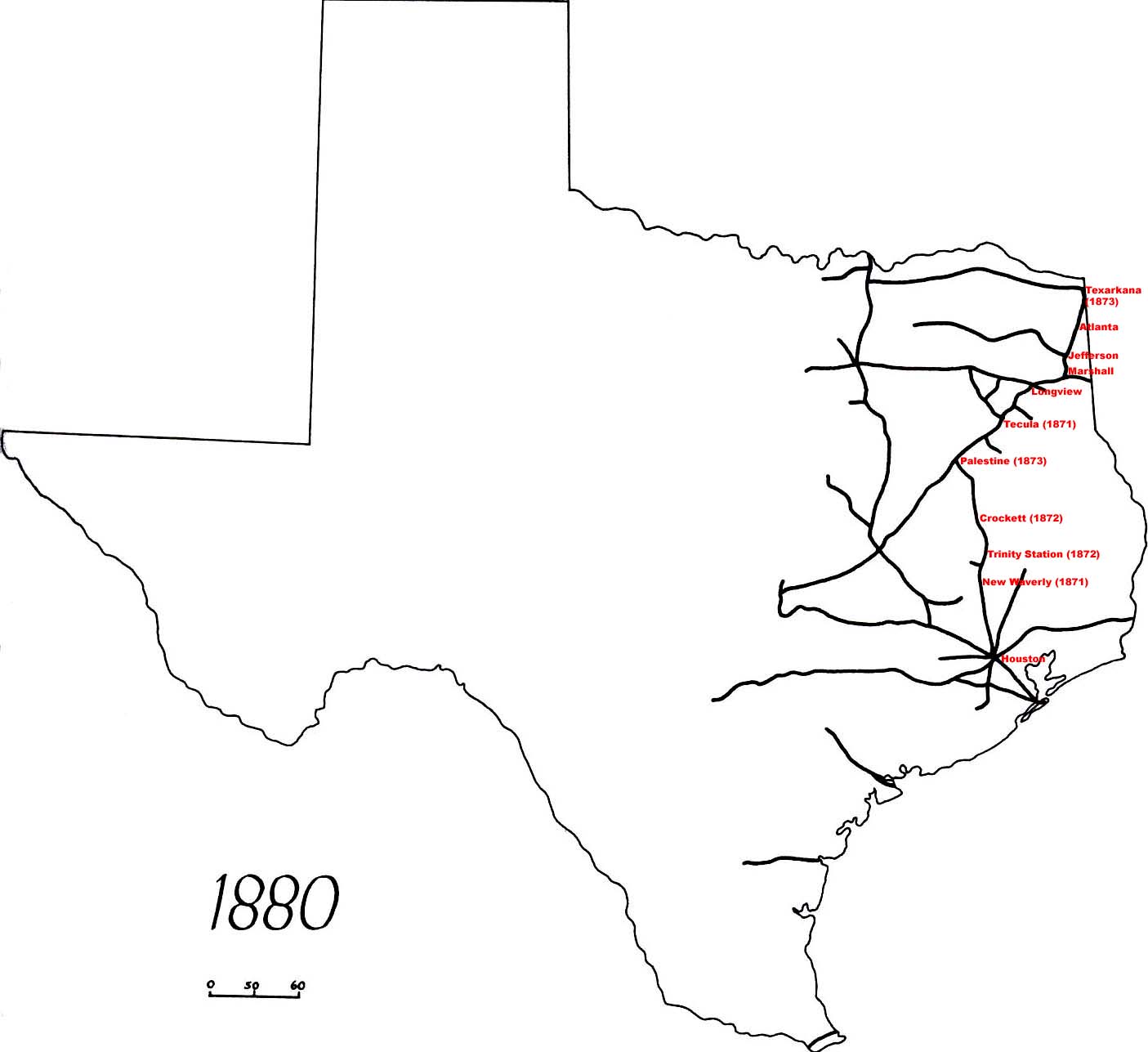

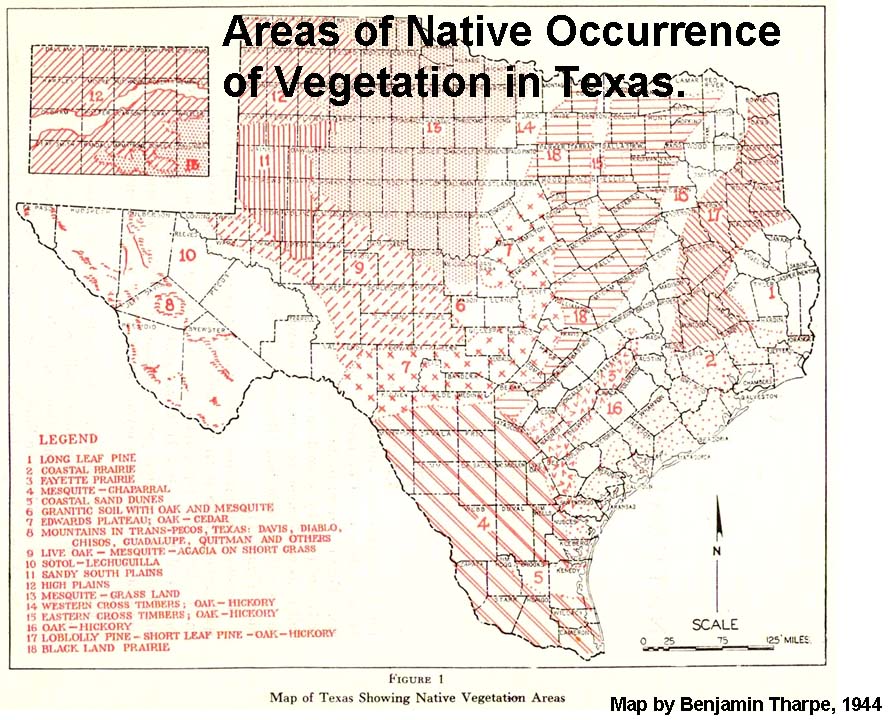

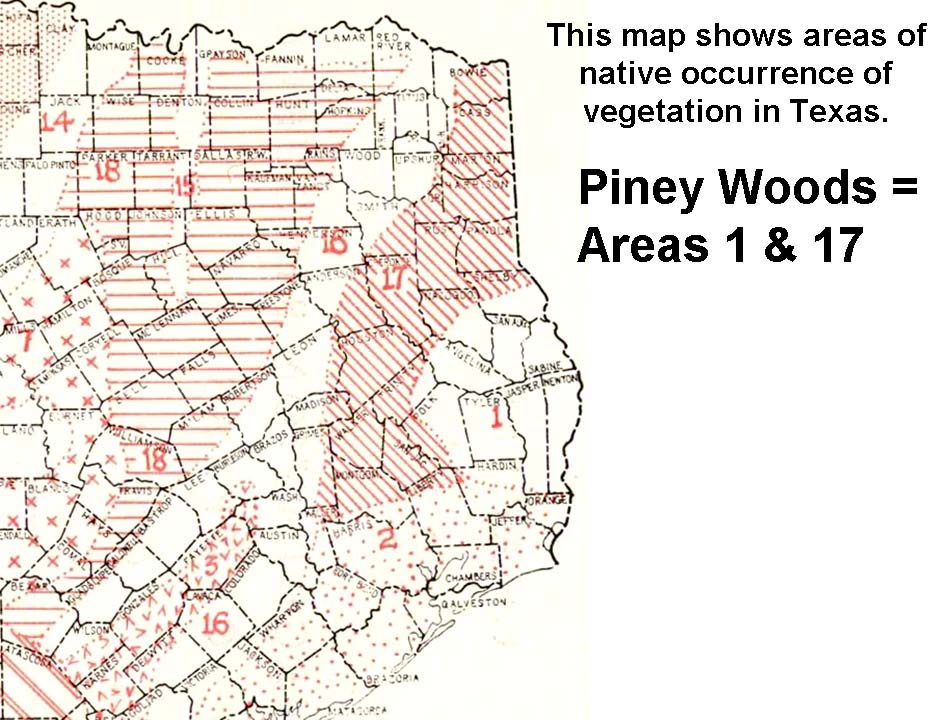

"Although the neighboring states of Arkansas, Louisiana, and Missouri would also produce boogie-woogie players and their boogie-woogie tunes, and despite the fact that Chicago would become known as the center for this music through such pianists as Jimmy Yancey, Albert Ammons, and Meade 'Lux" Lewis, Texas was home to an environment that fostered creation of boogie-style: the lumber, cattle, turpentine, and oil industries, all served by an expanding railway system from the northern corner of East Texas to the Gulf Coast and from the Louisiana border to Dallas and West Texas." (page 75)13 -- Dave Oliphant

Although there is an

obvious typographical error in his comments, in "Looking Up at Down: The

Emergence of Blues Culture,"76

William Barlow writes in Chapter 7, page 231:

"Piano players were the first blues musicians associated

with the Deep Ellum tenderloin. In Dallas, Houston, and other cities of

Eastern Texas, the prevailing piano style of uptempo blues numbers was called

"Fast Western" or "Fast Texas." An offshoot of boogie woogie, it probably

came from the "Piney Woods" lumber and turpentine camps based in northwest

Texas, northern Louisiana, and southern Arkansas. However, the style

became a fixture in "Deep Ellum" after the turn of the century."

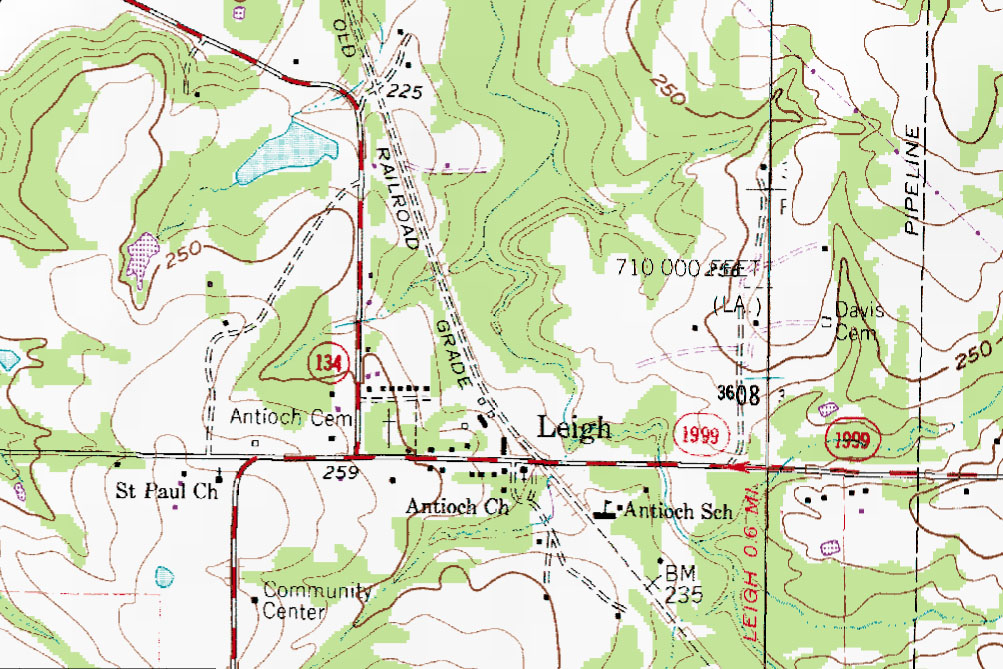

Barlow obviously meant to write "northeast Texas," as there were no "Piney

Woods" or "turpentine camps" in "northwest Texas." This typo is also

obvious in that it is "northeast Texas" that is at the confluence of

"northern Louisiana" and "southern Arkansas", an area currently known as

the Arklatex. These comments on the origin of Boogie Woogie by Barlow is

consistent with the 1899 witnessing by Leadbelly, as well as with the account

given by Lee Ree Sullivan of Texarkana.

Moreover, since piano players were the "first blues musicians" in Deep Ellum,

Barlow's comments suggest that Blind Lemon Jefferson might have borrowed his

"Booga Rooga" guitar bass figure from Boogie Woogie pianists in Deep Ellum,

but given travels with Lead Belly on the T&P line, Jefferson could have also

heard such Boogie Woogie pianists at other locations in Texas. Jefferson

might have also derived his "Booga Rooga" bass line from Lead Belly,

after Leadbelly witnessed Boogie Woogie bass lines played by pianists in the

Arklatex.

The Focus of My Inquiry into Boogie Woogie

The quotations above from E. Simms Campbell and Clarence Williams are among the earliest accounts that attribute an origin of Boogie Woogie music to a specific geographical region, namely Texas. Their comments above are also noteworthy in that neither E. Simms Campbell nor Clarence Williams were from Texas. Campbell was from St. Louis and spent time living and conducting research in both Chicago and New York. Williams was from Louisiana, and also spent considerable time living in Chicago and New York. Thus, neither man had a conflict of interest or a Texas bias that might have contributed to a distortion in their thinking about the geographical origin of Boogie Woogie. Moreover, in 1986, after many years of researching the development of the Blues in America, historian Paul Oliver corroborated the idea that Boogie Woogie music originated in Texas (See below). Consequently, part of my current analysis will focus on looking at evidence and at the music and migratory patterns of early Texas Boogie Woogie players. At the same time, I want to see if it is possible to account for other early reports of the performance of Boogie Woogie that seem to be geographically discontinuous with the preponderance of early reports. In summary, I hope to engage in a sort of "meta-analysis" that will yield a coherent theory for development of Boogie Woogie that takes into account all known evidence.

I will describe the musical features that distinguish Boogie Woogie. Moreover, when appropriate, I will also take the opportunity to defend the musicality of and dispel misconceptions about Boogie Woogie.

Ultimately, I want to consider Boogie Woogie in a much broader context of human evolution and universal aesthetic sensibilities. Part of this broader consideration will examine how the formal elements of Boogie Woogie have strong correlates and associations with ancient spiritual, religious, and sexual practices.

Another attribution of the geographical origin of Boogie Woogie to Texas was in the radio script, "The Boogie Woogie Beat: Rompin' Stompin' Rhythm," (broadcast the week of 1/17/02, Riverwalk script ©2001 by Margaret Moos Pick). Moos wrote [when referring to the developers of the Boogie Woogie]:

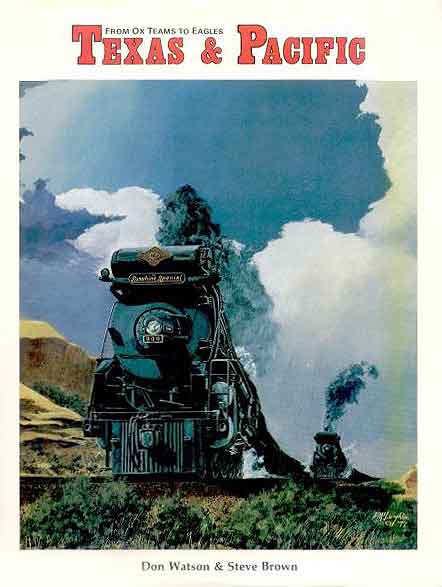

"They had a captive audience: loggers from the lumber camps deep in the piney woods, and workers laying track for the Texas and Pacific railroad, carving a line of steel through the wilderness. The sounds of barrelhouse Boogie Woogie spread out in all directions following the path of the newly emerging railroad lines."

Steam Locomotives Sang the Blues & Inspired Early Boogie Woogie Musicians

In the book, "The Story of the Blues," on page 16 in

his chapter titled “Cottonfield Hollers,”5

historian Paul Oliver wrote:

On page 170 (Chapter 4 "Lonesome

Whistles") of the book, "The Land Where the Blues Began,"27

Alan Lomax, wrote:

Pictured above is the Texas & Pacific steam locomotive 55, an A-2 Class 4-4-0 manufactured by the Schenectady company. The first steam locomotives used by the Texas & Pacific were built by Rogers Locomotive Works. For an excellent website pertaining to the Texas & Pacific Railway, see http://www.texaspacificrailway.org. For two excellent websites pertaining to general information about steam locomotives, including the Texas & Pacific, see http://www.steamlocomotive.com and http://www.steamlocomotive.info.

In the 1986 television broadcast of Britain's "South Bank Show" about Boogie Woogie19, music historian, Paul Oliver, noted:

"Now the conductors were used to the logging camp pianists clamoring aboard, telling them a few stories, jumping off the train, getting into another logging camp, and playing again for eight hours, barrelhouse. In this way the music got around -- all through Texas -- and eventually, of course, out of Texas. Now when this new form of piano music came from Texas, it moved out towards Louisiana. It was brought by people like George Thomas, an early pianist who was already living in New Orleans by about 1910 and writing "New Orleans Hop Scop Blues," which really has some of the characteristics of the music that we came to know as Boogie."19

Logging Train in the Piney Woods of East Texas

(From the East Texas Research Center Collection)

“The Boogie Woogie piano players had already developed a mature style in the early twenties, yet it waited until 1938 to find ready acceptance in the hot music field, and by such dispensers of musical taste as the arrangers.” – Frederick Ramsey, Jr. and Charles Edward Smith, 1939, page xiv in the "Introduction" to the book, “Jazzmen: The Story of Hot Jazz Told in the Lives of the Men Who Created It.”1

Hersal Thomas (sitting) & Older Brother George Thomas (standing)

(The image above appears on the cover of the CD album "Texas Piano, Vol. 1" by Document Records.)

If anyone knows of any other pictures of George or Hersal Thomas other than those displayed in this article, please contact me at nonjohn@nonjohn.com.

The Forward of the 1942 sheet music book, "5 Boogie Woogie Piano Solos by All-Star Composers,"12 edited by Frank Paparelli, states:

"This book features for the first time, the works of George and Hersal Thomas. They are credited with discovering the Boogie Woogie style."

According to music historian, Paul Oliver, this "discovery" was made in East Texas by George W. Thomas, Jr.5

Specifically, on page 85 of the book, "The Story of the Blues," Oliver writes that George W. Thomas “composed the theme of the New Orleans Hop Scop Blues – in spite of its title – based on the blues he had heard played by the pianists of East Texas.”5

On February 12, 2007, Paul Oliver confirmed to me that it was Sippie Wallace who told him that performances by East Texas pianists had formed the basis for George Thomas's "Hop Scop Blues." Moreover, Paul Oliver also indicated to me that Sippie had not been specific as to the locations in East Texas at which George Thomas witnessed these pianists.77

(However, in my upcoming book, I will provide an analysis of all evidence that I have collected to develop a coherent theory of the most probable locations within Texas where George and Hersal could have been exposed to specific musical elements later seen in "New Orleans Hop Scop Blues," "The Fives," and "The Rocks," and other pieces by the Thomas brothers.)

What is a "Barrelhouse?"

Above is a barrelhouse of the sort where Boogie Woogie was born.

When discussing the "barrelhouse" style of Boogie Woogie pianist, Robert Shaw, the Texas Handbook of History gives the following description of a "barrelhouse:"

"The style was named for the barrelhouses, where it was performed-sheds with walls lined with beer and whiskey, an open floor, and a piano on a raised platform in a corner of the room. The back of the barrelhouse was also used as a bawdy house."

Hersal Thomas: King of Chicago's House-Rent

"Boogie" Party Pianists

Hersal Thomas was an immense influence on other pianists,

including Albert Ammons, Meade Lux Lewis, Jimmy Yancey, and many others.

Many elements that we now know as elements of "Boogie Woogie" can be traced to Hersal and George Thomas' "The Fives."

Definitions of Boogie Woogie

The New Harvard Dictionary of Music2, 1986, defines "Boogie Woogie" as "a piano blues style featuring percussive ostinato accompaniments" that involve "steadily repeated bass patterns, one or two bars long" that "delineate the 12-bar blues progression, sometimes with IV in measure 2 or 10." This dictionary also states, "Melodies range from series of repeated figures reinforcing the explicit beat (including tremolos, riffs, rapid triplets) to polyrhythmic improvisations."

In 1987, Smithsonian music historian Martin Williams wrote (page 50)38:

"Boogie woogie is a percussive blues piano style--no one knows how old--in which an ostinato bass figure, usually (but not always) played eight beats to the bar, is juxtaposed with a succession of right hand figures."

Like all succinct attempts to define Boogie Woogie, these are, by necessity, limited in detail. Yet, they provide a starting place to approach Boogie Woogie, and from which to consider instances that defy these definitions. (For a more detailed consideration of Boogie Woogie's formal musical characteristics, see the "Tennison's Ten Boogie Woogie Elements" section below.)

How Old is Boogie Woogie?

In 1987, Martin Williams noted that "no one knows how old" Boogie Woogie is (page50).38

In 1995, Francis Davis wrote the following in "The History of the Blues" (page 151)7:

"Somewhere along the way -- no one knows for sure exactly when -- barrelhouse forked into boogie-woogie, an urban style characterized by eight insistent beats to the measure in the bass, and right-hand melodies that were essentially rhythmic variations on this bass line."7

With regard to the Boogie Woogie elements present in Pine Top Smith's "Boogie Woogie," in 1963, musical historian, Mack McCormick wrote:

"The term 'Fast Western' is unknown among Texas pianists. Moreover, they identify boogie woogie with the 1929 Pine Top smith record. They are, however, quick to point out that the elements Smith used had been common for decades."66

This account is consistent with Sammy Price's account40, which indicates that Blind Lemon Jefferson was playing Boogie Woogie bass figures on his guitar (which Jefferson called "booga rooga") before Pine Top Smith made his piano recordings.

However, despite Mack McCormick's learning that Robert Shaw was not familiar with the term, "Fast Western,"66 Lee Ree Sullivan of Texarkana told me in 1986 that he was familiar with "Fast Western" and "Fast Texas" as terms to refer to Boogie Woogie in general, but not to denote the use of any specific bass figure used in Boogie Woogie. Sullivan said that "Fast Western" and "Fast Texas" were terms that derived from the "Texas Western" Railroad Company of Harrison County, (formed on February 16, 1852), but which did not build track until after later changing its name to "Southern Pacific" on August 16, 1856. This Texas-based "Southern Pacific" was the first "Southern Pacific" railroad, and was in no way connected to the more well known "Southern Pacific" originating in San Francisco, California. Although the "Texas Western" Railroad Company changed its name to "Southern Pacific," Sullivan said the name "Texas Western" stuck among the slaves who were used to construct the first railway hub in northeast Texas. The Texas-based Southern Pacific Railroad was bought out by the newly-formed Texas and Pacific Railroad on March 21, 1872.

According to Sullivan, slaves had access to pianos on Sundays in some churches after the earlier morning services of white church-goers were completed. Sullivan said that, as far as he knew, prior to the Civil War, Sunday was the only day of the week on which slaves formally congregated at churches to play piano music in northeast Texas.68 Had such meetings not been in the context of practicing religion, antebellum access to pianos by slaves in northeast Texas would have probably been more limited. However, some slave narratives indicate informal access to pianos in non-scheduled contexts, such as in the homes of slaves owners.

The historical account of Clarence Williams indicates that George W. Thomas, Jr. was among the first, if not the first, to bring the musical elements of barrelhouses to urban performance. Williams noted that Thomas was playing "Hop Scop Blues" (later "New Orleans Hop Scop Blues") in Houston in 1911. George Thomas, Jr. was among the first to publish a Boogie Woogie broken-octave walking bass figure used in barrelhouses into written musical form in 1916. However, "The Weary Blues" by Artie Matthews (published in 1915) uses a Boogie Woogie broken-octave walking bass figure as well. So when Clarence Williams claims that "George Thomas was the fellow who used this style and first wrote it down,"63 it appears that having "wrote it down" does not refer to publishing, but rather having transcribed a Boogie Woogie broken-octave bass line.

Moreover, the Boogie Woogie broken-octave walking bass figure in Matthew's "The Weary Blues," is the same bass figure that Paul Oliver and others have identified as "The Cows" and as having originated in Texas."5 The bass figure known as "the cows" is a classic broken-octave Boogie Woogie walking-bass figure and can be heard in unison-octave form in the Cow Cow Davenport's "Cow Cow Blues" and in the open of Fats Waller's "Alligator Crawl." Although Waller was not known or playing or liking Boogie Woogie, he inserts "the cows" bass figure at 3 other places in "Alligator Crawl" besides the introduction.

In his book, "Ragtime: A Musical and Cultural History,"71 Edward A. Berlin has suggested that Blind Boone's 1909 "Southern Rag Medley 2"72 used a Boogie Woogie bass line in its "Alabama Bound" section. However, analysis of Boone's original sheet music, and analysis of Boone's 1912 piano roll performance of his "Southern Rag Medley 2," reveals that Boone's Alabama-bound bass line does not rise to the level of being a "Boogie Woogie" bass line. Specifically, Boone maintains a "duple-meter," "oom-pah" feel with his Alabama-bound broken-octave, bass line. Despite being "broken octaves" that "walk," Boone's broken octaves do not create a sense of ostinato, and his broken-octave bass notes remain harmonically subservient to the harmonic demands of the right hand, rather than achieve Boogie Woogie's sense of melodic and contrapuntal independence from the right hand part. Still, Boone's "Southern Rag Medley 2" is important in that this piece represents one of the earliest transcriptions of a transitional form suggestive of both Ragtime and Boogie Woogie. Moreover, in 1908 (the year prior to the publication of "Southern Rag Medley 2"), Scott Joplin used a broken octave bass line his "Pine Apple Rag." Yet, like Boone, Joplin's broken-octave bass line in "Pine Apple Rag" maintained a 2-4 "duple-meter," "2-to-the-bar," oom-pah feel, that was not independent, but rather, was harmonically constrained by the right hand part. Moreover, like "Pine Apple Rag," and "Southern Rag Medley 2", Artie Matthews's "Pastime Rag No. 1" (published in 1913) (See discussion below on different types of broken-octave bass lines.) also maintains a 2-4 "duple-meter," "2-to-the-bar," oom-pah feel, that is not independent, but rather, is harmonically constrained by the right hand part. Also, Matthews "broken-octaves" in "Pastime Rag No. 1" are grace-noted, the sort of "reverse-boogie" bass line that Eubie Blake uses in the 1917 piano roll recording of his "Charleston Rag." Not until Artie Matthews' 1915 publication of "The Weary Blues" do we have what rises to the level of having a "Boogie Woogie" broken-octave bass line, but with no inherent swing pulse. Yet, like George Thomas's "New Orleans Hop Scop Blues," the Boogie Woogie bass line of "The Weary Blues" is only present during part of the piece. Not until Jimmy Blythe's "Chicago Stomp" is there an example of (with the exception of the 4-measure introduction) a piece of music containing a Boogie Woogie bass line from beginning to end.

When Francis Davis says that "barrelhouse forked into boogie-woogie,"7 the word "forked" implies that some stylistic change might have occurred at the time of the "fork." However, no one to my knowledge has ever identified any specific stylistic elements that changed at a time of "forking." Thus, a more precise statement would have been to say that the music developed in the barrelhouses came later to be called Boogie Woogie when played in more urban environments. Moreover, despite Davis' description, not all Boogie Woogie is 8-to-the-bar, and right-hand parts of Boogie Woogie are not necessarily rhythmic variations of the bass line.

Even though the preponderance of evidence is consistent with an East Texas geographical origin for Boogie Woogie, historians do not have enough evidence to pin down the date of the very first occurrence of what could be called Boogie Woogie. However, besides McCormick's research indicated that Boogie Woogie elements used by Pine Top Smith "had been common for decades"66 before 1929, Sharon A. Pease (on page 8 of the October 15, 1939 issue of Down Beat Magazine83) noted the following in an article about Pinetop Smith:

"Pinetop cannot be given credit as the creator of the boogie-woogie style, for we know it has been played in the South as far back as the oldest residents can recall."83

Other than noting that they were the "oldest" residents, Sharon Pease was not specific about how many or which residents had been surveyed to determine that Boogie Woogie had been "....played in the South as far back as the oldest residents can recall."83 However, given the account of Elliot Paul, who noted: "And all the Old-time Texans, black or white, are agreed that boogie piano players were first heard in the lumber and turpentine camps, where nobody was at home at all. The style dates from the early 1870s.,"78 it is reasonable to conclude that Sharon A. Pease would have come to the same conclusion whether or not his survey was limited to African Americans. If the "oldest residents" as of October 15, 1939 to which Sharon Pease refers were solely African American, some of these African Americans would almost certainly have been old enough to have witnessed the piano performances of the early 1870s. Consequently, Sharon Pease's account is entirely consistent with Elliot Paul's account of Boogie Woogie, when Paul states,

"The style dates from the early 1870s."78

Moreover, by counting backwards from the ages of all known living African Americans who were alive as of the Down Beat article on October 15, 1939, it would be possible to derive a range of time prior to 1870 that African Americans in the population to which Sharon Pease referred could have potentially heard Boogie Woogie. Certainly, African musical sensibilities were present prior to 1870. However, prior to 1870, it is not clear whether they were being expressed on piano as influenced by the sounds associated with steam locomotives. That is, if these musical sensibilities were being expressed solely on drums, such expression would not mark the formal beginning of "Boogie Woogie."

Nonetheless, the African musical elements that informed Boogie Woogie were surely present prior to the Civil War. Consequently, the earliest Boogie Woogie performances would have had the purest relationship to African musical elements of ostinato, polyrhythm, and improvisation. These earliest performances would have stood in contrast to the more-structured, composed, and sterilized Boogie Woogies that were introduced to white audiences on a large scale in the 1930s and 1940s.

Given the account of Elliot Paul; and given that Lead Belly witnessed Boogie Woogie in 1899 in the Arklatex; and given the North to South migration of the Thomas family; and given the Texas & Pacific headquarter in Marshall in the early 1870s; and given that Harrison County had the largest slave population in the state of Texas; and given the fact that the best-documented and largest-scale turpentine camps in Texas did not occur until after 1900 in Southeast Texas, it is most probable that Boogie Woogie spread from Northeast to Southeast Texas, rather than from Southeast to Northeast Texas, or by having developed diffusely with an even density over all of the piney woods of East Texas. It would not be surprising if there was as yet undiscovered evidence of the earliest Boogie Woogie performances buried (metaphorically or literally) in Northeast Texas.

June 19, 1865 -- "Juneteenth" -- A Turning Point in the Development of Boogie Woogie

My inquiry into the "origin" of Boogie Woogie within the United States will focus mainly on evidence of when West African percussive ostinato styles and improvised percussive lead parts came to be applied to pianos in the United States. I make several assumptions that I hope are true. First, I assume that slaves had limited access to pianos prior to the end of the Civil War. In general, musical activities of slaves were limited, as these activities were believed by plantation owners to be capable of inciting riots and rebellions. Thus, prior to the civil war, most slave owners would have limited intentional access by slaves to the luxury and high technology of pianos. However, there are almost certainly exceptions to this assumption. Indeed, in these exceptions could lie the origins of Boogie Woogie.

Moreover, even before the Civil War was over, slave labor was used in Texas for construction of railroad tracks. Thus, the sounds of steam locomotives could have served as musical inspiration even before African Americans had easy access to pianos.

Nonetheless, most of my inquiry into the origin of Boogie Woogie will be concerned with events that followed the Civil War. Since a preponderance of evidence points towards a Texas origin for Boogie Woogie, I will focus largely on events following June 19, 1865. This date is known as "Juneteenth" in Texas because it is the date that "Union soldiers, led by Major General Gordon Granger, landed at Galveston, Texas with news that the war had ended and that the enslaved were now free."49 Consequently, this date would have been a significant transitional date at which time African Americans in Texas gained knowledge of their new freedoms and, thus, had the potential to make dramatic changes in four areas:

1. Expressing Freedom of travel

2. Engaging in musical expression and experimentation

3. Communicating musical ideas with each other

4. Greater access to pianos and other items of previously limited availability

Thus, the development of Boogie Woogie could proceed at a significantly faster rate after June 19, 1865.

Other events prior to June 19, 1865 that were relevant to the development of Boogie Woogie were the sounds of steam locomotives. These sounds would have been heard by slaves working on railroad construction. Moreover, slave owners would not have been able or desirous of censoring slaves from hearing these sounds. Moreover, these sounds would have occurred where tracks were being built and where steam locomotives were running.

In summary, the "origins" of Boogie Woogie that I will consider most will be those events that occurred from June 19, 1865 to 1900. Although Boogie Woogie continued to develop and evolve after 1900, various pieces of evidence, such as Lead Belly's account of piano walking bass lines in 1899, have resulted in my tendency to refer to Boogie Woogie events prior to 1900 as "origin" events, while referring to events after 1900 as "developmental" events. I recognize that such a division is arbitrary, as the development of Boogie Woogie, like most things in our macroscopic world (in contrast to quantum physics), is continuous and has no naturally-identifiable boundaries between historical eras. That is, the eras are all in our minds and only serve as convenient ways to divide time so as to create a nomenclature to have meaningful verbal communication with each other.

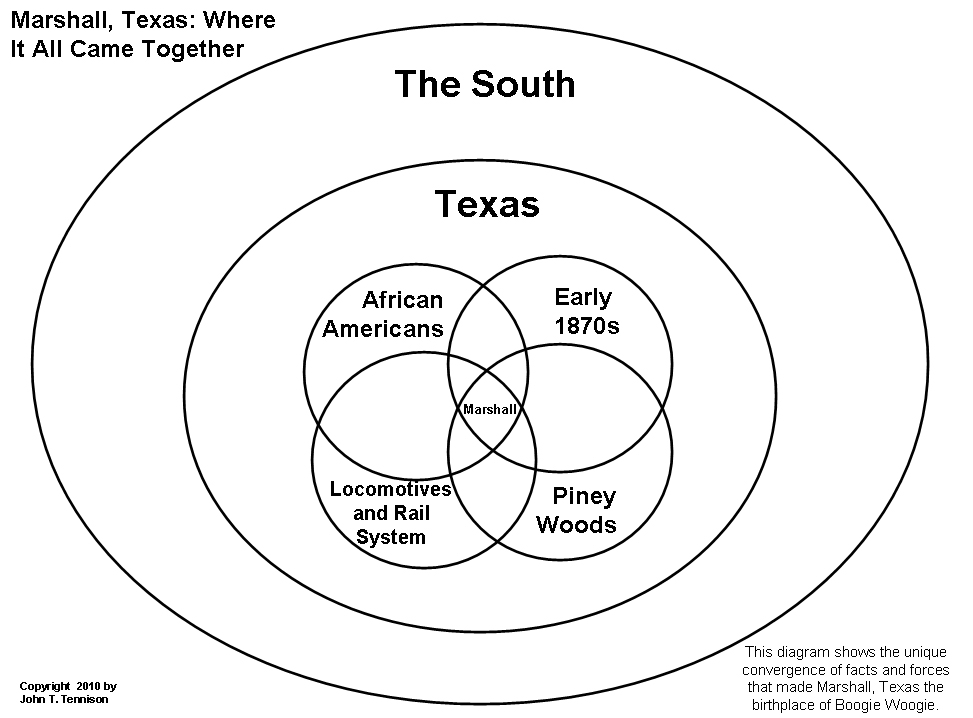

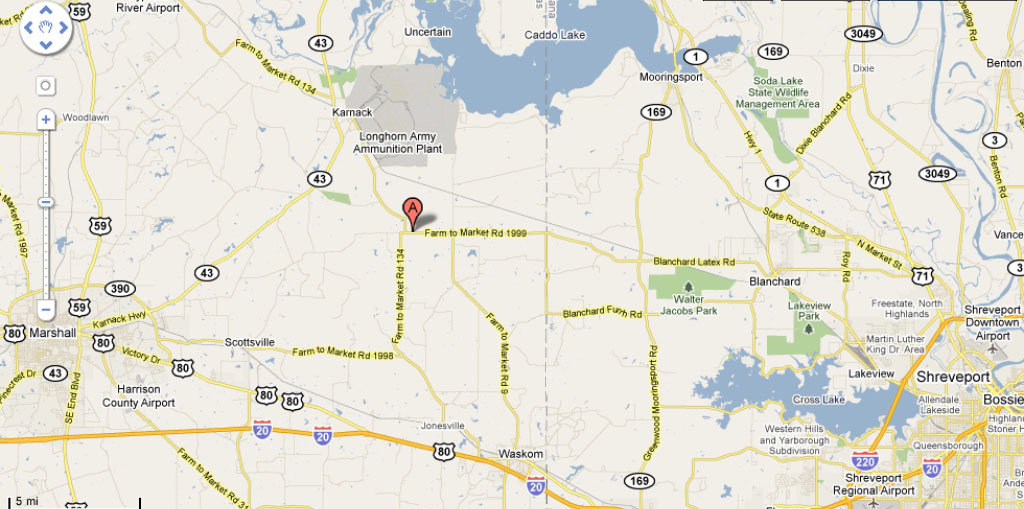

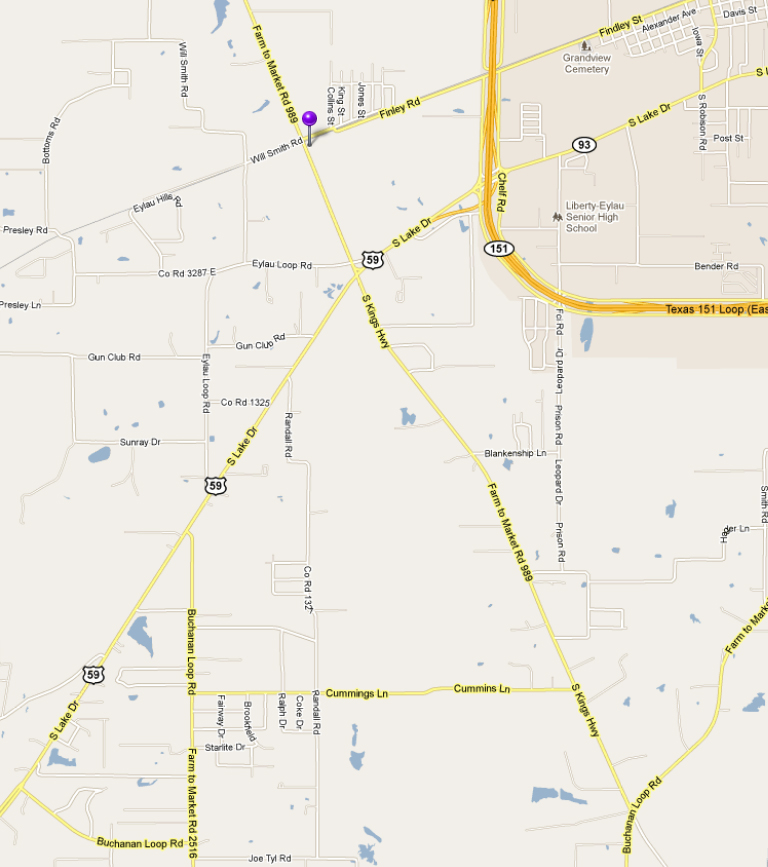

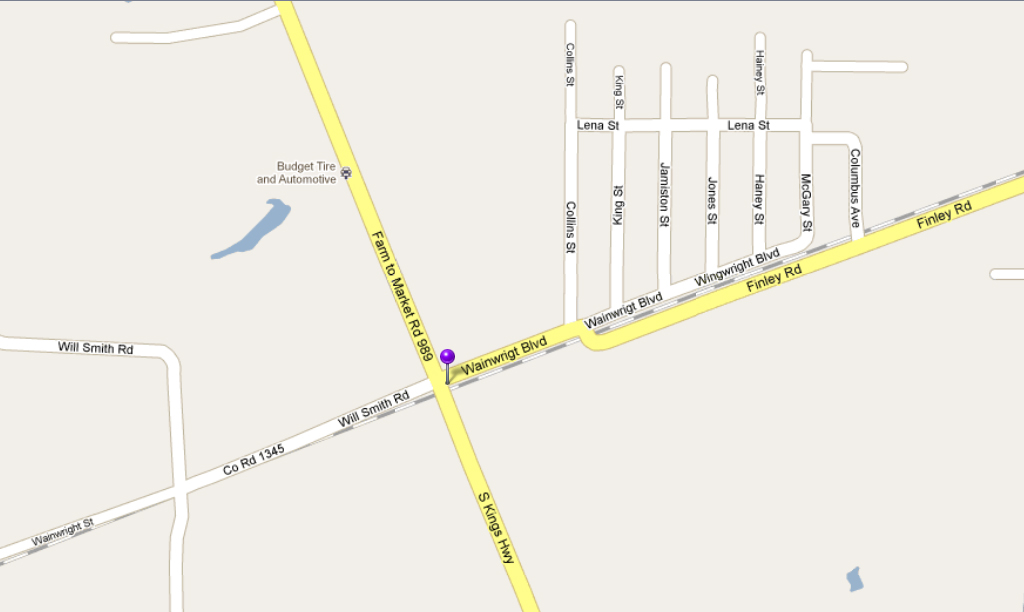

Marshall, Texas: The Birthplace of Boogie Woogie

Pictured above are the Texas & Pacific Shops in Marshall, Texas, the "Birthplace of Boogie Woogie" and earliest "Hub of Boogie Woogie"

When I call Marshall the "birthplace of Boogie Woogie", I define "birthplace" as "the municipality whose boundaries are most likely to encompass or be closest to the point on the map which is the geographic center of gravity for all instances of Boogie Woogie performance between 1870 and 1875." Moreover, I also regard Marshall as the earliest "Hub of Boogie Woogie," the crossroads with the most railroad traffic in the Piney Woods of East Texas, where the paths of the earliest itinerant Boogie Woogie musicians most frequently intersected, resulting in further development of the Boogie Woogie style. This railroad traffic resulted from Marshall having been the original headquarters and hub for the Texas and Pacific Railroad since the early 1870s. The Texas & Pacific Railroad both manufactured and repaired steam locomotives in Marshall, Texas.

On May 13, 2010, the city commissioners of Marshall unanimously passed an ordinance which declared Marshall, Texas the birthplace of Boogie Woogie.

After the early 1870s and before 1900, the center of gravity of Boogie Woogie performance appears to have shifted northward to Texarkana.68 This center of gravity continued to move northward, and by the 1920s, had become centered in Chicago.

Omar Sharriff (AKA David Alexander Elam) Brought the Boogie Woogie Home to Marshall, Texas

This photo of Omar Sharriff (AKA Dave Alexander Elam) was taken by John Tennison on June 11, 2010 in front of Sharriff's alma mater, the historic Pemberton High School in Marshall, Texas.

Omar Sharriff was born “David Alexander Elam” on March, 10, 1938 in Shreveport, Louisiana. The 1940 U. S. Census shows Omar (then known as David Elam) living with his family at age 2 at the street address of 2128 Marion Street in Shreveport, Louisiana. The 1940 census indicates that Omar's father, Tommy; mother, Susy; and 6-month old brother, Donald were also living at that same address in Shreveport at the time of the 1940 U.S. census. The 1940 U. S. Census indicates both of Omar's parents as having been born in Louisiana. However, this is possibly in error, as another document suggests that Omar's father, Tom Elam (AKA Tommy Elam), was born in Tatum, Texas, in 1893. Moreover, the 1940 U. S. Census indicates that Tommy Elam was 45 years old, but gives a birth year of "about 1895," suggesting that even at the time the census was taken, the census taker was expressing uncertainty about the birth year of Tommy Elam, which would also imply uncertainty about Tommy Elam's age. Consequently, at this time, I will express the birth year of Tom Elam (AKA Tommy Elam) as "circa 1893-1895."

After the 1940 U.S. Census was taken, Omar's family moved to a rural community in Harrison County Texas, just outside and south of Marshall and on the east side of Highway 59. Omar attended elementary school in this community before his family moved within the Marshall city limits, where Omar attended Pemberton High School. After being away from Marshall for many years, Omar Sharriff moved back to Marshall, Texas in 2011, where he lived for almost a year before his death on January 8, 2012.

Contemporary Keyboard Magazine First Annual Readers' Poll

In the first-ever Readers' Poll results, published on page 25 of the January, 1977 issue of Contemporary Keyboard magazine (later known as Keyboard Magazine), Omar Sharriff (then known as Dave Alexander) was ranked 2nd only to Ray Charles as the greatest living blues pianist. It is noteworthy to point out that Dave Alexander was ranked above other great living blues pianists at the time, including Professor Longhair (3rd place) , Memphis Slim (4th place) , Champion Jack Dupree (tied for 5th place), and Piano Red (tied for 5th place).

Omar's father, Tom Elam (AKA Tommy Elam) (born circa 1893-1895), was the first person that Sharriff ever heard play Boogie Woogie. Tom Elam was possibly born in Tatum, Texas, not far from Marshall. Sharriff's Boogie Woogie homecoming concert on June 11, 2010, represented a historical turning point, namely that of formally recognizing and publicly supporting the continuing performance of Boogie Woogie in Marshall, Texas, the Birthplace of Boogie Woogie.

Some confusion has existed over the years as to the identity of Sharriff's biological father. At least one published account25 has stated that Omar was the son of David Alexander (AKA Black Ivory King), who also spent time performing in the Arklatex and who recorded 4 pieces in Dallas, Texas. However, in a phone interview on October 25, 2010, with Jack Canson of Marshall, Texas, Sharriff stated that he was not the biological son of David Alexander (Black Ivory King). Rather, Sharriff stated that his mother, Susie (possibly spelled "Susy") Hill, named him after Black Ivory King at the request of Sharriff's father, Tom Elam, who was friends with David Alexander (Black Ivory King). Interestingly, Lead Belly has also cited David Alexander (Black Ivory King) as the name of a pianist who Lead Belly encountered90, most likely in the Arklatex area. Specifically, in 1970, on page 12 of his Down Beat article, "Illuminating The Leadbelly Legend," Ross Russell wrote:

"Leadbelly also heard pianists named Pine Top Williams, Dave Alexander, and Dave Sessom of Houston, Tex., although he was not sure if he heard them in 1906 or later in his travels."90

The First Railroad between Texas and Another State

The first inter-state railroad between Texas and another state was the line running between Marshall, Texas and Shreveport, Louisiana. This line was created in 1863 when the Southern Pacific built tracks to the state line between Texas & Louisiana, where tracks continued onward to Shreveport. The Texas portion of this line was created by the Southern Pacific, which was absorbed into the Texas & Pacific in 1872.

The figure above is from Charles Zlatokovich's book, "Texas Railroads". The first inter-state railroad between Texas and another state (Louisiana) can be seen meeting the Texas border in the northeast portion of the state of Texas. The towns on this line (from west to east) included Longview, Hallsville, Marshall, Waskom, and Greenwood, and Shreveport.

The Texas & Pacific Railway Depot in Marshall, Texas

Pictured above is the refurbished Texas & Pacific Train Depot in Marshall, Texas

Pictured above is the recently refurbished (1999) Texas & Pacific Railway Depot in Marshall, Texas, site of a current-day Texas & Pacific Museum.

The Continuing Mystique of Steam: The Texas State Railroad

Still running as of 2009, the Texas State Railroad, which runs between Rusk and Palestine through the Piney Woods of East Texas, can give you an inkling of the experience that itinerant musicians might have had as they traveled through the woods from one barrelhouse to the next between 1870 and 1900 while sharing musical ideas that would make history. Palestine was one of the towns through which the Thomas family probably traveled when they migrated from Little Rock to Houston. At this time (between 1883 and 1898), Palestine was on the International and Great Northern Railway route, part of the Jay Gould system of Railroads. The Texas State Railroad runs the only Texas & Pacific locomotive still in operation as of 2009. It is a 4-6-0 "Ten Wheeler," which was Engine 316 when owned by Texas and Pacific, but now lives on renamed as Engine 201 on the Texas State Railroad. The 4-6-0 wheel configuration is the same type depicted on the cover of "The Fives'," by the Thomas Brothers. Consequently, to ride this particular Texas & Pacific locomotive in the Piney Woods of East Texas has strong symbolic meaning, but is also probably as close as one can come in 2009 to simultaneously experiencing the locomotive and natural environmental sounds of East Texas as heard by the itinerant musicians who created Boogie Woogie in East Texas.

Other Names by Which Boogie Woogie is Known

The developments in Boogie Woogie that occurred in Chicago in the 1920s, and at various places in the 1930s, resulted in a prototypical recordings or yardsticks by which other latter music can be compared to assess its "Boogie-Woogie-ness." Meade Lux Lewis, Albert Ammons, and Pete Johnson are exemplary Boogie Woogie exponents whose collection of recordings from the 1920s,1930s, and 1940s provide a yardstick to which other music can be compared to asses its Boogie-Woogie-ness. Although I prefer the term "Boogie Woogie," to describe music that resembles the prototypical sound of Ammons, Lewis, and Johnson, below are other terms that are sometimes used to refer to music that contains the formal elements of Boogie Woogie:

Fast Western - "Fast Western" appears to be the earliest term by which Boogie Woogie was known.85 "Fast Western" was cited as an early term for Boogie Woogie by E. Simms Campbell in 1939.1 The assertion that "Fast Western" was the earliest term by which Boogie Woogie was known was made by Max Harrison in 1959 when he wrote: "The music did not acquire the name 'boogie' for some time. At first it was called 'fast Western' -- another indication of its place of origin -- and it retained similar names when it travelled. Thus, when recalling his early days in Kansas City, Pete Johnson said all the pianists played 'the same sort of Western rolling blues."85 Rosetta Reitz corroborated the account of Pete Johnson, when she wrote: "Pete Johnson who grew up in Kansas City said they called it 'western rolling blues.'"74 "Fast Western" as the earliest term for Boogie Woogie was corroborated by Mack McCormick in the liner notes to his Treasury of Field Recordings, Vol. 2.86 McCormick came to this conclusion despite the fact that he found that Boogie Woogie pianists from the Houston area and from places other than the Arklatex were not familiar with the term "Fast Western" for Boogie Woogie. According to Lee Ree Sullivan of Texarkana, both "Fast Western" and "Fast Texas" derived from the "Texas Western Railroad," a precursor to what later became the Texas & Pacific Railroad.68 Thus, it appears most probable that "Fast Western" is a term for Boogie Woogie that emerged in the Marshall area of Harrison County, Texas in early 1870s, where Boogie Woogie was probably first played.

Fast Texas - usually used interchangeably with "Fast Western." See "Fast Western" above.

Fast Blues - as described by E. Simms Campbell in 1939, as contrasted with the "Slow Blues" of New Orleans1

Galveston Blues - In 1966, Victoria Spivey indicates that what had been called "The Galveston Blues" was "now called the 'Boogie Woogie.'"45

Barrelhouse - refers to the locations where much of early Boogie Woogie evolved. Literally speaking, "Barrelhouse" can refer to any music that was traditionally played in barrelhouses. Consequently, not all "Barrelhouse" music was Boogie Woogie. For example, some "Barrelhouse" music would have sounded more like Ragtime than Boogie Woogie. However, in present-day usage, "Barrelhouse" is used more often to refer to styles that sound more like Boogie Woogie and less like Ragtime. Sometimes the term "barrelhouse" is used to refer to music that is said to have proceeded but led to Boogie Woogie, yet, unless distinctions are made as to what musical elements distinguish this usage of "Barrelhouse" from Boogie Woogie, this is an ambiguous distinction. Many times "barrelhouse" is used to describe Boogie Woogie when it is played with the least structure of all, in which the player has no idea of what he or she is going to play until after starting to play. Such performances, as in the case of Alex Moore, are often accompanied by spontaneous commentary. When speaking of Boogie Woogie played on Fannin Street in Shreveport, Lead Belly stated, "Boogie Woogie was called barrelhouse in those days."87

Boogie - Sometimes uses as a contraction or synonym of "Boogie Woogie." However, sometimes used to refer to guitar renditions of a Boogie Woogie walking bass or a Boogie Woogie pulse, especially as was developed in Rockabilly and "Hillbilly" derivatives of Boogie Woogie.

Blues Piano - can refer to the fact that some Boogie Woogies use a 12-bar or other common cyclical harmonic progression used in blues music.

Dudlow Joe (AKA Dud Low Joe; AKA Dudlow) - Given considerable confusion I have encountered surrounding the term, "Dudlow Joe," an extended discussion of this term is warranted. According to Little Brother Montgomery and Willie Dixon, "Dudlow Joe" was a term used for Boogie Woogie in Mississippi when Little Brother Montgomery was about 12-13 years old, meaning 1918-1919.96 Given the accounts that indicate use of "Boogie," and "Boogie Woogie," prior to 1900, "Dudlow Joe" does not appear to predate "Boogie Woogie," or the still earlier "Fast Western" as a term for what we now know as Boogie Woogie. Moreover, in 1960, Montgomery seems to indicate that when he was nine years old, (circa 1915), the term "walkin' basses" was used to describe a Boogie Woogie bass figure.96 Montgomery also seems to indicate that "Dudlow Joe" did not become a term for Boogie Woogie until Montgomery was 12-13 years old.96 Specifically, in the 1965 book, "Conversation with the Blues," (based on field recordings made by Paul Oliver from June through September in 1960 (page xvii)96), Montgomery is quoted as having said the following on page 69-7096: "On up I learned another blues from a great guy name of Loomis Gibson. We called it the Loomis Gibson Blues which is the name of it. When I first tried to play it I was only around the age of nine so I used to only play a walking bass with one finger then, but after I got up around twelve or fourteen I could double up and I could play with all of my hand. Later on, Loomis Gibson passed and I named it the Crescent City Blues. We used to call it walkin' basses at the time, but we never called it anything special. I was playin' what you call boogie woogies ever since I was twelve or fourteen years old but then we called it Dud Low Joe."96 In contrast to the 1965 "Conversation with the Blues" book, the 1965 co-released LP of the field recordings made in 1960 by Paul Oliver contain liner notes which quote Montgomery saying the following: "....- oh I were playin' boogie-woogies ever since I were twelve or thirteen years old. We used to call it walkin' basses at the time...(piano solo)...we called it Dud Low Joe." Thus, it appears that the 1965 book publication of "Conversation with the Blues," and even the later 1997 Cambridge University Press re-publication of the "Conversation with the Blues" book contain a transcription error by having printed "fourteen" rather than "thirteen" years old.)

Other comments about "Dudlow Joe" from Little Brother Montgomery appear in the book, "Deep South Piano: The Story of Little Brother Montgomery," by Karl Gert zur Heide, 1970, Studio Vista Publishing97. On page 18, Karl Gert zur Heide wrote that, with regard to Boogie Woogie bass figures, Little Brother Montgomery stated the following: "We were playing all those kind of basses down there, way before ever it came out on records. I used to only play a walking bass with one finger then, but after I got up around twelve, fourteen I could double up and play with all of my hand. We called it Dudlow Joe."97 Also on page 18 of his book, Karl Gert zur Heide writes that Willie Dixon stated the following: "They used to call boogie piano Dudlow Joes in Mississippi. I didn't hear it called boogie till long after. If a guy played boogie piano they'd say he was a Dudlow player. Later on guitars played boogie too."97 On page 33 of his book, Karl Gert zur Heide writes that Willie Dixon, who was born in 1915 in Vicksburg, Mississippi, stated the following: "When I was a little boy in Mississippi, I used to run around and follow the bands through the streets."97 and "They had a band up on the back of a truck and I loved it. I remember Little Brother up on the truck playing piano. You've got to hear him do Farish Street Jive. It's the most beautiful thing. Years ago they called it Dudlow."97 Also on page 33 of his book, Karl Gert zur Heide states: "Little Brother's commentary upon hearing Lee Green's Dud-Low Joe was: 'He's trying to play Farish Street Jive.'"97 Thus, Montgomery's and Dixon's accounts indicate that the term "Boogie Woogie" and "Fast Western" had not yet become part of the vernacular of Montgomery's circle of piano players circa 1918-1919. A common misconception that I have encountered is the mistaken belief that Montgomery and/or Dixon claimed that Boogie Woogie originated in Mississippi. Examination of their quotes from the Paul Oliver interview and the Karl Gert zur Heide biography reveal that neither of them made such a claim.

However, in the 1989 biography of Willie Dixon ("I Am The Blues: The Willie Dixon Story," by Willie Dixon with Don Snowden)98, Dixon does make additional specific claims which are ridiculous and unbelievable. For example, on page 5 of the 1989 biography, Willie Dixon states: "They call it the old 12 bar blues because people like Little Brother Montgomery and other guys started putting a left hand boogie beat to 'em. In those days, if the beat wasn't uptempo, they called it 'barrelhouse' and if it was uptempo, they called it 'Dudlow' or 'Dudlow Joe.' They would call this left hand putting the dudlow to the blues." and (also on page 5 of the 1989 Dixon Biography): "After people got wise enough to commercialize it, somebody said, 'Well, we'll call this boogie-woogie.' That gave everybody a chance to say, 'This is my boogie and that's his boogie.' If they kept calling boogie-woogie 'dudlow,' then it would have been based on black folks' music.' When they began calling it boogie-woogie, it creates the feeling of a certain thing anybody can do."98 First, it should be pointed out that Dixon is not claiming that Montgomery originated left-handed Boogie Woogie bass figures, but rather that "Montgomery and other guys" were ones who started playing such bass figures in the context of a 12-bar blues structure. However, given that Dixon was not born until 1915, and given that Montgomery was not born until 1906, even this claim is unbelievable because of accounts of Boogie Woogie bass figures having been played with structures involving 12 bars and various other numbers of bars prior to 1900. Of course, whether such structures prior to the birth of Montgomery could be considered "blues" structures is a matter of definition, but it is almost certainly the case that the elements used to accompany Boogie Woogie bass figures prior to 1906 had characteristics that would have easily been considered "blues" by modern definitions. Moreover, Dixon's claim that the use of "barrelhouse" referred to music that "wasn't uptempo" is not a universal way of using the term "barrelhouse," as there are plenty of instances where the term "barrelhouse" is used more generally to describe any music that happened to be played in a barrrelhouse, be it slow or fast. However, the most ridiculous and unbelievable claim that Dixon makes is when he suggests that the term "boogie-woogie" was first used as a result of a desire to commercialize the music. This claim is at odds with multiple accounts which demonstrate that the music was being called "Boogie Woogie" by African Americans, whose use of "Boogie Woogie" had nothing to do whatsoever with a desire to "commercialize" the music. Of course, there was a substantial commercialization of the term "Boogie Woogie" in the 1940s, but this came well after the term "Boogie Woogie" had become part of the African American vernacular for non-commercial reasons. Moreover, Dixon makes the absurd claim that calling the music "boogie-woogie" would give the impression that the music was less "based on black folks' music" than would occur if the music was called "dudlow." Amazingly, Dixon seems oblivious to the fact that the breakthrough recording that popularized the term "Boogie Woogie" to larger numbers of people than ever before was Pine Top Smith's Boogie Woogie, which was a "race" record marketed primarily to African Americans, and for which record companies had no motivation to obscure the fact that Pine Top Smith was African American or that Pine Top Smith's Boogie Woogie was a style of music played predominantly by African Americans at that time. However, in the later case of "Tommy Dorsey's Boogie Woogie," there probably was an intent to sterilize and obscure the black origins of the music to make it palatable for white audiences, but the use of "Boogie Woogie" in the title did not serve that function.

Lastly, despite an extensive interview of Little Brother Montgomery, Paul Oliver's research led him to the conclusion that Boogie Woogie had originated in Texas. Similarly, after extensive interviews of both Little Brother Montgomery and Willie Dixon, Karl Gert zur Heide's wrote the following about the origin of Boogie Woogie on page 11 of his book: "The earliest reports hint at an origin somewhere between New Orleans and Dallas, Memphis and Houston, but Mississippi and Alabama also had strong boogie traditions."97 Karl Gert zur Heide's descriptions of an origin "somewhere between New Orleans and Dallas, Memphis and Houston"97 is fully consistent with my conclusion that Marshall, Texas is the most probable municipal geographical center of gravity of the earliest Boogie Woogie performances, especially when one considers the earliest railroad corridors that created a connection between the four cities of New Orleans, Dallas, Memphis, and Houston. For example, the Texas and Pacific Railroad was the primary railroad corridor between "New Orleans and Dallas", and the earliest primary railroad corridor between "Memphis and Houston" included the Texas and Pacific tracks between Texarkana and Marshall, Texas, and the Texas and Pacific tracks between Marshall and Longview, Texas. Moreover the common track between the Dallas-New Orleans corridor and the Memphis-Houston corridor was the Texas and Pacific track between Marshall and Longview, Texas.

Country Blues (Piano) - Sometimes used as a contrast to urban blues, such as those with the Harlem Stride oom-pah bass lines.

Honky Tonk - suggests a location and the sound of a train, as in "Honky Tonk Train"

Ragtime - can refer to the syncopation (i.e. the "ragged time") used in Boogie Woogie and Ragtime. Yet, Boogie Woogie usually does not have a oom-pah left hand as its predominant bass figure as Ragtime typically does.

Walking Bass - What Sammy Price said Boogie Woogie was called in Texas while, at the same time, being called "booga-rooga" by Blind Lemon Jefferson (This usage pre-dated the recording of "Pine Top's Boogie Woogie.") Also, Little Brother Montgomery seems to indicate that "walkin' basses" was a term used prior to "Dudlow Joe" among Montgomery's circle of Boogie Woogie players.96 Of course, not all Boogie Woogie bass figures are walking basses. Walking basses tend to be heard melodically and thus contrapuntal to right-hand parts, but because of their width and close harmonies of their chords, stride basses (see below) tend not to be perceived as melodic, but rather as harmonic accompaniment to right-hand parts.

Stride - as opposed to "Walk," refers to a relatively greater width between successive left hand notes and/or chords. Put another way, "Walking" basses and "Stride" basses are on the same continuum, with "Striding" being at one end and "Walking" being at the other end. Oom-pah strides are less common in Boogie Woogie, and more common in "Ragtime" and what is called "Stride Piano," as developed Harlem and New York City. In the movie, "Ray,"33 about the life of Ray Charles, the Ray Charles character indicates that he got his start playing "stride," yet this is a factual error. If the writers of this screenplay had stuck to the facts, they would have the Ray Charles Character say that he learned piano from a "Boogie Woogie" piano player, as the real-life Ray Charles indicated in his 1978 autobiography: "Sometimes I'm asked about my biggest musical influence as a kid. I always give one name: Mr. Wylie Pitman. I called him Mr. Pit."56 and (page 8) "Mr. Pit could play some sure-enough boogie-woogie piano."56 and (page 8) "Oh, that piano! It was an old, beat-up upright and the most wonderful contraption I had ever laid eyes on. Boogie-woogie was hot then, and it was the first style I was exposed to. Mr. Pit played with the best of them."56 Moreover, in an interview with Clint Eastwood in the "Blues Piano"32 documentary in the "Martin Scorsese Presents the Blues" series, Charles also gives credit to Boogie Woogie as the style in which he first got his start. Thus, screenplay writers for the movie, "Ray,"33 were either ignorant, and/or wanted to promote the word "stride." Sadly, the only time the term "Boogie Woogie" occurs in the film, "Ray," is when it is uttered in a derogatory fashion by a racist white member of a country band when he indicates to the Ray Charles character that the country band does not play any "Boogie Woogie." Thus, the movie adds to the confusion of what is meant by "Boogie Woogie." Still, "Ray" is an excellent film that beautifully depicts the discovery by young Ray of, Mr. Wylie Pitman (A.K.A. "Mr. Pit"), the Boogie Woogie player who kindly gave Ray his first piano lessons.33

Swing - Many Boogie Woogies have a swing (A.K.A. shuffled) feel to them, yet "Swing" also often refers to a sort of high-brow, urbanized, orchestrated, ensemble music that often lacks the ferocity of raw Boogie Woogie.

Jazz - Jazz is the most non-specific of all terms used to refer to Boogie Woogie. (See section bellow titled, "Is Boogie Woogie Jazz?") For the four reasons listed below, Boogie Woogie is Jazz, but so are a lot of other styles of music! Thus, calling Boogie Woogie "Jazz" is true, but not very specific.

Rock and Roll Piano - Think Jerry Lee Lewis or Little Richard! What they played was essentially Boogie Woogie with the addition of vocals, guitars, and drums.

Rockabilly - Sometimes used to describe the use of a Boogie Woogie beats, pulses, bass lines (often adapted to guitar) in country music that emerged in the 1940s and that (in addition to the direct influence of piano-based Boogie Woogie) influenced such artists as Jerry Lee Lewis and Chuck Berry, both of whom consider their own music to be a form of Boogie Woogie.

Hillbilly - Sometimes used interchangeably with "Rockabilly" Moon Mullican (AKA "King of the Hillbilly Pianists") is an example of a white performer who played Boogie Woogie, influenced Jerry Lee Lewis, and brought Boogie Woogie to the Nashville country music scene.

8-to-the-Bar - Refers to the number of pulses per measure, although not all Boogie Woogie is 8-to-the-bar. 8-to-the-bar is in contrast to Ragtime's 2-to-the-bar (AKA oom-pah).

Sixteen - term used by Eubie Blake to refer to 16 notes in the left hand for every 4 in the right. However, Blake's account of the use of this term might have been concocted. (See section below on Eubie Blake.)

The Sacred & Profane: Boogie Woogie, Jazz, Sex, Trance, Spirituality, & Existentialism

Historians must decide the arbitrary starting date at which they want to start making their historical inquiries and analysis. That is, every effect has its cause, which is the effect of a still earlier cause. With regard to the "origin" of Boogie Woogie, I could easily say that Boogie Woogie had its origins in West African ostinato percussive traditions underlying improvised lead percussive parts. Moreover, these traditions existed prior to the slave trade to the Americas. In turn, these percussive traditions had their origins (causes) in still earlier facts of human biology. That is, improvised lead parts played on top of an ostinato substrate resonated with primitive humans for reasons that are almost certainly intrinsic to our evolutionary and sexual biology.

Ostinato (a repeating musical pattern, such as a melody and/or rhythm) probably had its first, primitive appeal because it sounded like three things:

1. A heartbeat

2. Breathing

3. The in-and-out or back-and-forth movement of sexual intercourse

Accelerating ostinato probably had its first, primitive appeal because all three of the factors above accelerate during sexual intercourse.

Improvised lead percussive parts probably had their first, primitive appeal because such parts sounded like the randomness, unpredictability, surprise, delight, and loss of control during orgasm and ejaculation.

In the book, Texan Jazz13, Chapter 4, titled, "Boogie Woogie," page 75, author Dave Oliphant writes, "Barrelhouse, boogie-woogie, and jazz all originate to some degree in the religio-sexual customs of primitive African societies, for Wilfrid Mellers (page 273)14 notes, one of the meanings of the phrase 'boogie-woogie,' and of the word 'jazz' itself, is sexual intercourse, even as the ritualistic-orgiastic nature of the music also represents an ecstatic form of a spiritual order." A quotation of the complete paragraph in the Mellers chapter cited by Oliphant reveals one of the most eloquent descriptions of the relatedness between Boogie Woogie and sexuality that I have read. In his 1964 book, “Music in a New Found Land: Themes and Developments in the History of American Music14,” in the chapter, “Orgy and alienation: country blues, barrelhouse piano, and piano rag,” Wilfrid Mellers writes on pages 273-274:

“Not surprisingly, considering where it was played, barrelhouse piano is an extremely sexy music in which the incessant beat and thrust of the boogie rhythm become synonymous with male potency. However confused and confusing its etymology may be, there is no doubt that one of the meanings of the phrase boogie-woogie, as of the word jazz itself, is sexual intercourse; and what happens in the music is both descriptive and aphrodisiac. Thus the obsessively repeated rhythmic figurations of the “riff” phrase adapt a primitive orgiastic technique to the bar-parlour: while both the repetitions and the perpetual cross-rhythms of the right hand brace the body and the nerves against the forward thrust. The deeper implications of the act of coition come in, too, because in the relationship between the two voices or rather hands there is both a duality of tension, and also a desperate desire for unity which would, of its nature, destroy the forward momentum, make Time stop. From this point of view the significance of the break is interesting. Technically, it is simply a rest for the pianist’s hard-stomping left hand; but it becomes, in the explosion of its cross-rhythms, literally a break in Time – a kind of seizure within the music’s momentum. In this sense its effect is like an orgasm: though it is never finally resolutory. The piano blues is a communal act in that it is meant to be performed in public places; but the orgasm into which the listeners, along with the pianist, are “sent” remains as private, if elemental, as it would be when enacted in the room upstairs.”14

and (page 274):

“Boogie-woogie is a sensual celebration, too: but its creators, far from being lords of the earth, had nothing to celebrate but their own animal vigour.”14Wilfrid Mellers also writes (page 276):

"The Negro’s obsession with the railroad has become a twentieth-century myth. The railway train—powerful at the head, snake-like in elongation—is probably a phallic image; and the railway also opened up and ravished the American wilderness. Although it represented an endless series of departures, there was always the hope that one might arrive somewhere wonderful at the end. The Negro himself worked on the railroad, and rode on it legitimately or as hobo; in any case he was a traveler moved on by economic necessity, living in the mere fact of motion because he had little else to live for. In Honky Tonk Train Blues the thrust of the chunky left-hand triads generates an immense momentum, which is enhanced by the right hand’s fantastically complex (though of course intuitive) cross-rhythms. The interlocked energy of the rhythms is vigorously sexual; but again the orgasm is incomplete. We cannot conceive of motion except in relation to passion, feeling, growth; here, we are “sent” by the rhythm into a state of trance because we experience it without reference to melody or even harmony—for the note-clusters are, for the most part, percussive dissonances. For this reason, the motion itself becomes a kind of immobility; and the piece ends, through inanition, in the same way as Indiana Avenue Stomp. The train chuffs to stillness, just as the pendulum of the stomp’s clock surrenders motion. This is indicated in the conventional fade-out on the flat seventh. Barrelhouse blues hardly ever end in tonic resolution, and Jimmy Yancey, what key he was playing in, tended to doodle out on the flat seventh of E flat. He was still traveling, never really at journey’s end.”14

The accelerating chugging sound of a steam locomotive is an ecstatic, orgasmic sound that naturally resembles the human sexual excitation cycle as described by researchers Masters and Johnson. The chugging sound resembles the sound of human breathing and of perspiring bodies slapping together. After the steam locomotive is fully accelerated, the blowing of its whistle is analogous to the human orgasm. The slowing down of the steam locomotive as it pulls into the station is analogous to the slowing in breathing and refractory period between human sexual orgasms. A train wreck or boiler explosion is analogous to having a heart attack and orgasm at the same time, following by immediate death, as tragically happens from time to time.

When speaking of Boogie Woogie as played in the late 1920s, music historian Giles Oakley wrote in his book, “The Devil’s Music: A History of the Blues:”24

“Both the music and the word boogie had been around for years; brothels were called boogie houses, and to ‘pitch a boogie’ could mean to throw a party, or something more sexual, but it was the 1928 recording of Pine Top’s Boogie-Woogie by Pine Top Smith which pinned the name to this rough, driving piano style.”24

Texas Boogie Woogie pianist, Robert Shaw, said the following in 1963 in the liner notes to his "Texas Barrelhouse Piano" album (Previously released on Mack McCormick's Almanac label):

"When you listen to what I'm playing, you got to see in your mind all them gals out there swinging their butts and getting the mens excited. Otherwise you ain't got the music rightly understood. I could sit there and throw my hands down and make them gals do anything. I told them when to shake it, and when to hold it back. That's what this music is for."46

The fact that Ragtime and Boogie Woogie were the soundtracks of brothels is evidence of their role in representing, accompanying, and evoking sexual feelings and behaviors. In contrast, highly-orchestrated, urban incarnations of Boogie Woogie are often sterile and deny Boogie Woogie’s origins in raw sexual drives, feelings, and behaviors. Pure, raw, Boogie Woogie performed with its greatest degree of virtuosity always remains sexually aware. To not have this awareness or lose touch with one's own sexuality during the performance results in a less intense, less virtuosic, and less musically pleasing performance.

Occasionally, I will hear a music critic suggest that discussing the sexual relatedness of Boogie Woogie is an attempt to de-legitimize the musicality of Boogie Woogie. Such criticism usually comes from someone who is uncomfortable with or who has a fear of public discussions of sexuality. That is, someone's negative attitude towards sexuality, NOT sexuality itself, creates the mis-perception that sexuality de-legitimizes music. In this instance, fear, not sexuality, is the de-legitimizing factor. I would argue instead that relatedness to sexuality (whether or not it is conscious) legitimizes, empowers, and builds a unassailable foundation for Boogie Woogie.

In contrast, the decrease in creativity and dis-empowering effects of de-emphasizing sexuality is conveyed by the words of Sigmund Freud, who wrote:

"My impression is that sexual abstinence does not promote the development of energetic, independent men of action, original thinkers or bold innovators and reformers; far more frequently it develops well-behaved weaklings who are subsequently lost in the great multitude."

Moreover, along with the "profane," the "sacred" is always present. Revealing the inseparable connectedness between the "profanity" and the "sacredness" of Boogie Woogie demonstrates its universality and consequently, increases its legitimacy.

A poignant example of Boogie Woogie's dual role in a "sacred" and "profane" environments comes from T-Bone Walker, the first well-known electric blues guitarist. Walker was born in northeast Texas in Linden, in the same far northeast region of Texas as Scott Joplin. Walker's influence on later artists, such as B. B. King, is profound and obvious. In fact, much of what is called B. B. King's "Delta Blues" comes from East Texas. Listening to the early recordings of T-Bone Walker will leave no doubts to this claim.

In 1913, Walker heard Boogie Woogie being played in his church in Dallas. So, clearly, not all churches considered Boogie Woogie to be evil or "the Devil's music." Although T-Bone was a guitar player, Boogie Woogie's influence can be heard in much of his music, as can be heard in his "Hypin' Women Blues," which incorporates prominent Boogie Woogie piano, and "profane" lyrics about streets filled with women looking for romance.

The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame website quotes Mahalia Jackson, who said, "Rock and roll was stolen out of the sanctified church!" What was stolen was not so much the Gospel lyrics, but rather, the intensity of Boogie Woogie and other forms of music performed in African American churches. Indeed, the only significant differences between some African American Gospel music and secular African American Blues Music are the lyrics and the behaviors encouraged or associated with each genre of music. The quality and intensity of the emotions felt during each genre of music are often indistinguishable, demonstrating once again an inseparable connection between the sacred and the profane. Thus, although Boogie Woogie might not have always occurred in the context of a specific belief system of an organized religion, Boogie Woogie does provide what scholars, such as William James, have called "religious experiences."48

Besides Boogie Woogie's and Jazz's inextricable sexual and spiritual relatedness, these styles of music are also intimately related to American existentialism. This connection was passionately conveyed in the writings of Normal Mailer. In the book, “Existentialism,”3 Editor Robert C. Solomon in 1974 (University of Texas) wrote:

“In a long series of brilliant and discomforting novels and essays

Norman Mailer has given us the first explicit formulation of what might well be

called American existentialism. This

is not to say that it has held an appropriate position in American intellectual

life. But given the difference

between the role of the intellect in French and American life, it is not

surprising that American existential should find its home in jazz and in the

streets, Whether or not we consider it worthwhile to attempt a comparison

between Mailer’s existentialism and the philosophical theses we have

presented, it is undeniable that Mailer’s writings offer us the best American

expression of the existential attitude we have to date.”

In his 1957 essay, “The White Negro,“4 Mailer writes:

“Knowing in the cells of his existence that life was war, nothing but war, the Negro (all exceptions admitted) could rarely afford the sophisticated inhibitions of civilization, and so he kept for his survival the art of the primitive, he lived in the enormous present, he subsisted for his Saturday night kicks, relinquishing the pleasures of the mind for the more obligatory pleasures of the body, and in his music he gave voice to the character and quality of his existence, to his rage and the infinite variations of joy, lust, languor, growl, cramp, pinch, scream and despair of his orgasm. For Jazz is orgasm, it is the music of orgasm, good orgasm and bad, and so it spoke across a nation, it had the communication of art even where it was watered, perverted, corrupted, and almost killed, it spoke in no matter what laundered popular way of instantaneous existential states to which some whites could respond, it was indeed a communication by art because it said, 'I feel this, and now you do too.'”4

(Note: In 1957, Mailer’s use of the word, “Negro,” was not considered a racial epithet or in any way meant to be derogatory. If he were writing the essay in 2004, he very well might have substituted the expression “African American” for the word “Negro.”)

Is Boogie Woogie "Jazz?" Yes! Absolutely!

There is a war of words in which some want to co-opt the word “jazz” to apply only to the music that they own, promote, play, or otherwise stand to benefit from. Sometimes this approach results in "defining" Boogie Woogie outside of the scope of "jazz." However, when analyzed carefully, there is no question that Boogie Woogie has historically been considered a form of Jazz in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, and should still be regarded as jazz in present times.

Not only has Boogie Woogie traditionally been considered as a form of jazz, Boogie Woogie has been considered one of the most impressive forms of jazz. For example, in 1936, English jazz reviewer, John Goldman wrote the following in Swing Music Magazine about Meade Lux Lewis's recordings37:

"I believe that Meade Lux Lewis is not only the most interesting musician in jazz today, but of yesterday also. Moreover, unlike the others, he will not date: unlike any of the others, he is as much of any other age as this age."37

and

"You will probably be immediately struck by Meade Lux Lewis's curious left hand. I was. I hadn't heard anything like it in jazz before."37

These John Goldman comments are quoted in Chapter 7 (page 133) of Peter Silvester's book, The Story of Boogie Woogie: A Left Hand Like God9.

Not until the 1950s, did Boogie Woogie start to lose some of its identity as Jazz when Boogie Woogie gained widespread exposure and re-labeling as "Rock and Roll."

However, even in 1987, The Smithsonian still included Meade Lux Lewis's "Honky Tonk Train Blues" in the "Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz."38

Moreover, there is no question that Boogie Woogie should still be considered a form of jazz, especially in improvisatory forms as practiced by modern-day Boogie Woogie composers. Furthermore, Boogie Woogie easily falls within modern definitions of jazz. To see why, consider this following analysis:

In Chapter 2, “What is Jazz” in “Jazz Styles: History and Analysis”15 (Seventh Edition) by Mark C. Gridley, the following is written on page 4:

“Many different kinds of music have

been called 'jazz.' So it is no

surprise that people cannot agree about how to define it.”

However,

Gridley enumerates the following possible definitions

of jazz, all of which are satisfied by Boogie Woogie (page7-8)15:

1.

“For many people, music need only be

associated with the jazz tradition to be called jazz.”

2.

“For many others, a performance need only convey

jazz swing feeling in order to be called jazz.”

3.

“For some people, a

performance need only be improvised in order

to qualify as jazz.”

4.

“The most common definition for jazz requires that a performance contain

improvisation and convey jazz swing feeling.”

Clearly, improvisatory Boogie Woogie easily satisfies all four of these definitions of Jazz. Thus, Boogie Woogie, especially when involving improvisation, is a form of Jazz. In fact, improvisatory Boogie Woogie in some ways is more truly "jazz" than what is being taught as "jazz" in formal school programs around the world. That is, to the extent that any music can be taught, it has lost some of its improvisational freedom, is being produced according to a set of rules, and is therefore less jazz-like, because its practitioners are not making up the rules as they go. The best Boogie Woogie players, however, improvise not only the specific notes they play, but also their harmonic progressions, and the number of bars for a given harmonic progression. Such broad improvisational freedom is greater than that in most music that is called "jazz," and can make it hard for jazz musicians who play pitched instruments to follow these Boogie Woogie performers, because the other jazz musicians playing pitched instruments are following the teaching of restricting themselves to a non-improvised number of bars, and non-improvised chord changes. In contrast, Jazz musicians who play non-pitched instruments, such as percussionists, can typically follow and sound good with an advanced Boogie Woogie player, while avoiding all of the unintended dissonances that result when players of two pitched instruments are unable to synchronize their improvised chord and other harmonic changes.

Similarities and Differences Between Boogie Woogie and Ragtime:

"They All Played Ragtime,"8 (But Only Some of Them Played Boogie Woogie)44

Although the words, “Boogie Woogie” and “Ragtime” have occasionally been used synonymously, there is no question that the modern meanings of these terms refer to different musical attributes. Nonetheless, some of the same sensibilities, especially in the right-hand parts, informed both Boogie Woogie and Ragtime.

Although his exact place of his birth is uncertain, evidence indicates that Scott Joplin, the Father of Ragtime, was born in Northeast Texas, somewhere between Texarkana and Marshall Texas, possibly near Linden, where his family was known to be living not long after Scott's birth. Scott Joplin's father moved the Joplin family to Texarkana so that Joplin's father could take a job with the Texas & Pacific Railroad. Scott Joplin took his first piano lessons in Texarkana. Joplin was known to have had a classically-trained German piano teacher, Julius Weiss, who was born in Saxony, circa 1840-1841. Weiss might very well have brought a Polka "oompah" rhythmic sensibility from the old country to Texarkana, Texas, where Joplin was his pupil.