Recall that in 1939, African American historian E. Simms Campbell wrote:

“Boogie Woogie piano playing originated in the lumber and turpentine camps of Texas and in the sporting houses of that state."

Also recall that Elliot Paul wrote the following on page 229 in 1957 (in Chapter 10 "Boogie Woogie ") in his book "That Crazy American Music":

"The first Negroes who played what is called boogie woogie, or house-rent music, and attracted attention in city slums where other Negroes held jam sessions, were from Texas. And all the Old-time Texans, black or white, are agreed that boogie piano players were first heard in the lumber and turpentine camps, where nobody was at home at all. The style dates from the early 1870s. Even before ragtime, with its characteristic syncopation and forward momentum, was picked up by whites in the North, boogie was a necessary factor in Negro existence wherever the struggle for an economic foothold had grouped the ex-slaves in segregated communities (mostly in water-front cities along the gulf, the Mississippi and its tributaries)."

Although there is very good reason to conclude that Boogie Woogie had its origin in logging and railroad-construction camps, there is also very good reason to conclude that Boogie Woogie did not have its origin in the camps where turpentine was being produced in the early 1870s. This is because such turpentine camps were only in the long-leaf Piney Woods of Southeast Texas, rather than being in the Piney-Woods logging camps of Northeast Texas, which, in the early 1870s, were already closely associated with a pre-existing railroad infrastructure, and with the construction of new railroad infrastructure. The opportunity for repetitive, sonic musical inspiration from the sound of multiple steam locomotives appears to not have existed in the turpentine camps of the early 1870s.

Not until the late 1870s does there appear to be railroad tracks laid in close proximity to where a turpentine camp might have existed. Two railroad companies were operating locomotives in proximity to where turpentine camps might have existed in the late 1870s. The first was the Houston East & West Texas Railroad, which had built track from Houston just over the Trinity River to southern Polk County (Goodrich) by 1879; and then to Moscow (in Central Polk County) by 1880. The other railroad company, which was much smaller, was the Yellow Bluff Tram Company in Jasper County. In 1878, The Yellow Bluff Tram Company began running a single locomotive on a short logging or "tram" road from Yellow Bluff on the Neches River to Buna (in Jasper County), where there was a logging camp. Perhaps inspired by knowledge of a steam locomotive having been brought by boat to Swanson's Landing on Caddo Lake in Harrison County about 20 years earlier, the single locomotive used by the Yellow Bluff Tram Company was transported by boat up the Neches River to Yellow Bluff where rails had been constructed to run in a south-easterly direction from Yellow Bluff towards Buna. Since this was a short, isolated railroad which was not connected with any other railroad infrastructure, logs cut along this line were dumped into the Neches River at Yellow Bluff and floated to Beaumont, Texas, for further processing in saw mills, and then distributed by rail and boat from Beaumont to other destinations.

The largest-scale turpentine production in close association with railroad infrastructure did not occur in Southeast Texas until after 1900. Moreover, the Southeastern counties of Texas where this turpentine production occurred had an African American population that was dwarfed by that of Harrison County throughout the 1800s and continuing on at least through 1960.

Thus, the claim that Boogie Woogie "originated," was "created" or "came from" turpentine camps is inconsistent with the above data, and with the fact that the numerous oral histories cited by Elliot Paul indicate the creation of Boogie Woogie in the early 1870s.

Other evidence that supports a Northeast Texas origin for Boogie Woogie comes from the fact that the earliest eyewitness accounts of the performance of Boogie Woogie in Texas or near Texas occur in in the area of the Arklatex, which includes Northeast, not Southeast Texas.

The Piney Woods of East Texas

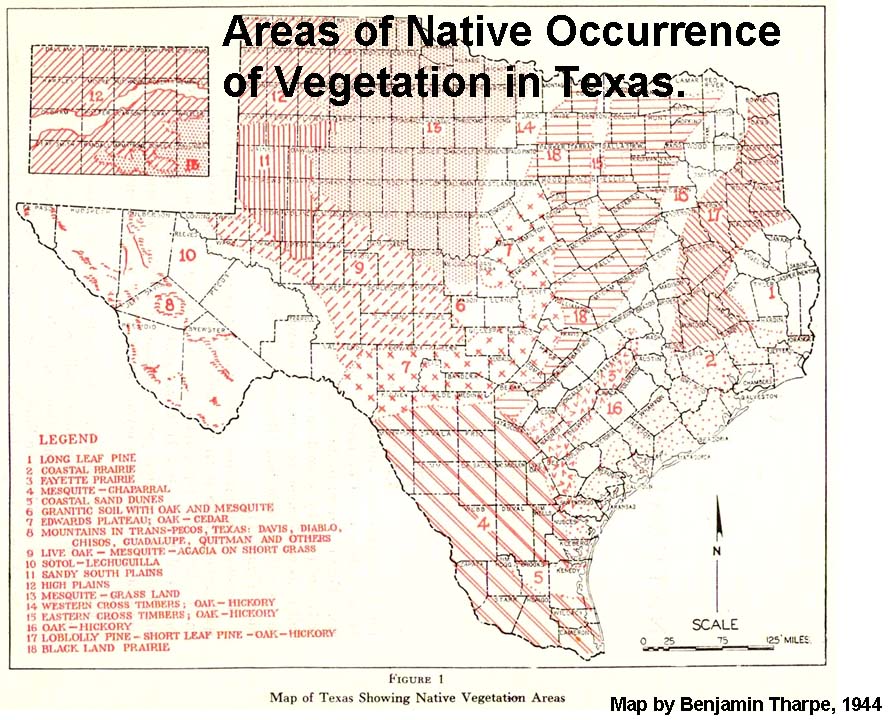

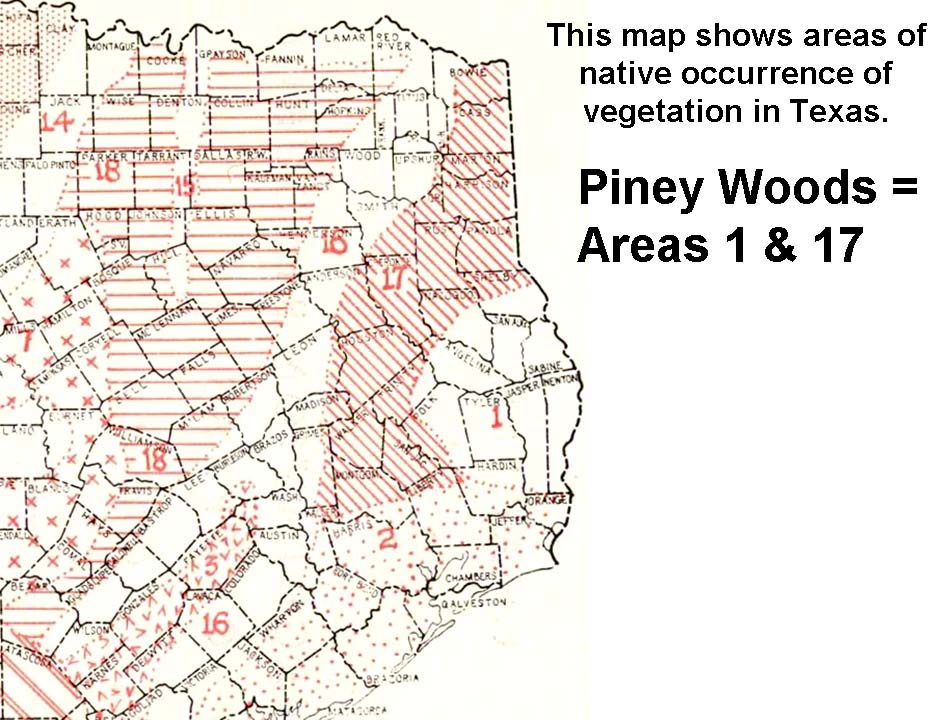

As can be seen in the legend above showing locations of native occurrence of Vegetation in Texas, Area 1 contained Long Leaf Pine, which is the source of turpentine. Area 17 contained Loblolly Pine, Short Leaf Pine (neither of which is typically used for turpentine production), as well as Oak and Hickory.

Above is a detail of Benjamin Tharpe's 1944 map, which shows the areas of native occurrence of vegetation in Texas. Areas 1 and 17 are the parts of Texas typically known as "The Piney Woods" of East Texas. As can be seen in the map above, there were 11 Texas Counties with significant Long Leaf Pine forests.

Nonetheless, it does appear that Boogie Woogie continued to undergo significant development in the turpentine camps that were established after 1900 in the Texas and Louisiana counties located in the long-leaf pine forests of Southeast Texas and Southwestern Louisiana. Consequently, based on Campbell's comment, a useful exercise would be to determine the earliest known instances of lumber camps, turpentine camps, and sporting houses in East Texas. Although lumber camps were fairly evenly distributed from north to south in the Piney Woods of East Texas, turpentine production would have been more prominent in the Southern part of the Piney Woods of East Texas because the Longleaf pine species is more common in the Southern part of the Piney Woods of East Texas. So if we were to consider ONLY turpentine production, it would seem make sense to conduct research in the southern half of the Piney Woods of East Texas. Yet, to consider only turpentine production would be to ignore the other earlier correlates of Boogie Woogie that point towards a Northeast Texas origin.

The other potentially important qualifying word in Campbell's account is "camps." Obviously, there could have been small turpentine production operations that did not involve "camps." However, without a sufficient size of operation, there would have been less pressure on owners of such camps to bring pianos for the musical entertainment of a small work force. Consequently, itinerant musicians would have been more likely to have frequented camps with enough critical mass of workers, and would have been more likely to have frequented camps with connections to other camps by way of a rail system.

After searching for references to turpentine production in pre-1900 Texas, the Texas Almanac from 1867 (published by The Galveston News) proved to have some useful information.

In the section on Hardin County (p. 122), the 1867 Texas Almanac states: "We have one turpentine manufactory, and tar is also an article of trade. Our pine and other timber is inexhaustible, and will constitute an important article of trade when our facilities of transportation are improved."

In the section on Trinity County (p. 163), the 1867 Texas Almanac states: "One turpentine manufactory was started during the war; and several steam grist and saw-mills are already in successful operation, and are rapidly making fortunes for their owners." The most likely location of this "turpentine manufactory" was Sebastopol, which was on the Trinity River, downstream from what would later become "Trinity Station" when the International Railroad arrived in Trinity County in 1872.

Another historical account by Bob Bowman indicates the presence of turpentine distilleries in the towns of "Bold Springs" and "Patonia" (in Polk County) on the Trinity River downstream from where Sebastopol was located in Trinity County. Because of the locations of the Polk County turpentine distilleries, they would have been less likely than Sebastopol to have had interaction with a railroad in the early 1870s, specifically the International Railroad at Trinity Station. Not until the Houston East & West Texas Railroad built to Polk County from Houston in the late 1870s would the turpentine distilleries of "Bold Springs" and "Patonia" have been as close to significant railroad infrastructure as was the turpentine distillery at Sebastopol as of 1872.

Trinity Station: The Closest Railroad to East-Texas Turpentine Camps in the Early 1870s

To the extent that turpentine was still in production in Trinity County in 1873, turpentine camps in Trinity County that supported such operations would have seemingly been in closer proximity to those travelling on the Texas & Pacific railroad tracks, as compared to turpentine camps in any of the other 10 counties in Texas with significant Long Leaf Pine forests. This likelihood of this proximity was due to the fact that the "International Railroad" had completed its line between Longview (on the T&P line) and Houston in 1873. The completion of this line occurred in 1873 when tracks that had been built southward from Longview (on the T&P line) met up with tracks in Palestine that had been built northward from Houston. Upon completion of this line, the very first north-south railroad network in East Texas from Texarkana to Houston was established. (From Texarkana to Longview, the tracks were those of the Texas & Pacific, and then from Longview to Houston, the tracks were those of the International Railroad.) With the exception of the area in north Harris County and south Montgomery County, all of this north-south route was contained completely within the Piney Woods of East Texas.

Before reaching the southward-going tracks at Palestine to the north, the International Railroad line had created "Trinity Station" when it built through far western Trinity County in 1872. However, most of Trinity County (see map above) is not composed of Long Leaf Pines. I have not found any records to indicated that turpentine camps in Trinity County in the early 1870s had a rail connection to Trinity Station. Thus travel to turpentine camps from Trinity Station in the early 1870s would have been over land and not by rail. However, the Trinity & Sabine Railroad (established in 1881), built from Trinity (previously "Trinity Station") eastward 38 miles ("Milepost 38") by 1882. Then, the Trinity & Sabine Railroad was absorbed by the Missouri, Kansas & Texas Railroad in 1882. By 1884 the track running eastward from Trinity had been extended from Milepost 38 to Colmesneil (in northern Tyler County). Thus, this eastward-going track from Trinity made possible direct rail travel into the heart of the Long Leaf Pine forests from Trinity. Thus, a railroad network was created where iterant musicians could travel eastward directly by rail from Trinity into close proximity of any turpentine camps that were near that eastward running line.

It should be noted that the word "manufactory" implies an area where distillation of turpentine was taking place, but not necessarily the same location where a turpentine "camp" was located.

In the section on Tyler County (p. 165), the 1867 Texas Almanac states: "The lumber and turpentine business would prove lucrative here." Note that this sentence does not state that turpentine production or camps already existed in Tyler County.

In the section on Jefferson County (p. 165), the 1867 Texas Almanac states: "The exports before the war were about as 4 to 1 since. There have been exported during the year ending August 31st, 1866, cotton, 6500 bales; cattle, 4760 head; rosin, 855 bbls.; spirits turpentine, 100 bbls.; beef hides, 10,000; lumber, 3,000,000 feet; shingles, 1,040,000." Note that this sentence does not state that turpentine specifically was one fourth that of pre-war production, but rather, than overall "exports" were one fourth the amount of pre-war "exports."

In her article (which uses the 1867 Texas Almanac as a reference) on Jefferson County (located in the Southeast corner of Texas), Diana J. Kleiner indicates that there was some turpentine production in Texas prior to the Civil War when she writes the following about the effects of the Civil War on Jefferson County:

"After the war the county population declined to 1,906 by 1870. Although African Americans held a few government offices and blacks and whites were both politically active as voters during the federal election of 1888, blacks were all but totally disfranchised in the federal election of 1892. Recovery from the war was slow. Jefferson County exports in 1867 of cotton, cattle, beef hides, lumber, cypress shingles, and lumber products including resin and turpentine constituted only about one-fourth of their prewar total [appears to be citing the 1867 Texas Almanac]. Sugar production between 1860 and 1880 was limited, and significant agriculture did not develop again until after 1890. By 1876, however, the county was once again a lumber and shipping center, as loggers used the Neches and Sabine rivers to float logs to mills at Orange and Beaumont, where mills manufactured 82,000,000 shingles and 75,000,000 board feet of timber by 1880. Exports, including pine for cross-ties and bridges, made these towns major lumber centers by 1900."

Since current-day Orange County, Texas, was carved from Jefferson County on January 5, 1852, some of the pre-Civil-War production of turpentine attributed to Jefferson County could have been occurring in what is present-day Orange County, Texas. Whether or not turpentine camps in Jefferson County or Orange County contained piano players in the 1860s is uncertain. If anyone knows of any evidence of piano performances at turpentine camps in Southeast Texas prior to 1900, I would love to hear from you at nonjohn@yahoo.com.

Since the largest-scale turpentine camps in Texas occurred after 1900, and since Boogie Woogie appears to have its origin in the early 1870s, I inquired with Bob Bowman about pre-1900 turpentine camps. Bowman wrote the following back to me on July 26, 2005:

"There isn't a lot of history about turpentine camps; I don't think I've ever seen a complete list of the old camps, and I am nearly 70 years old."

and

"Some of the lumber companies were in business in the early 1880s, and those in the longleaf pine forests usually operated turpentine camps before they starting cutting the trees."

Based on this information from Bob Bowman, we could infer the existence of pre-1900 turpentine camps in proximity to, but not necessarily in the exact same locations to wherever longleaf Pine lumber camps existed. Turpentiners first drained longleaf pines of resin from which turpentine was distilled, and then later, loggers moved in to cut the trees down. Since virgin longleaf pines were fairly evenly distributed within the longleaf pine forests, since resin from longleaf pines and felled pines were transported convergently to the camps, present-day areas of smaller-diameter, new-growth longleaf pines, or areas of less density of trees among areas of greater density could potentially be used to predict approximate locations of previously-undocumented turpentine or logging camps. However, given the extensive clear-cutting that has occurred, such an approach might yield highly imprecise results, if at all. With a high-enough resolution, early aerial photos might also be useful in such an inquiry.